It’s the start of the new academic year, and the Greenfield Digital Center is looking forward to greeting returning students and giving a special welcome to those of you who are on campus for the first time. We know it took a lot to get here. Have you ever wondered what it would have been like to apply to college 120 years ago? Last year we published a series of early entrance examinations from the Seven Sisters, the schools (including Bryn Mawr College) that defined prestigious women’s education in the late nineteenth century. Though the institutions were all founded with slightly varying visions, they were set apart as a group from earlier models of women’s education by their mission to provide academically rigorous schooling that led to a degree. For the first time, women were being offered an academic experience that was comparable to that enjoyed by men.1

It’s the start of the new academic year, and the Greenfield Digital Center is looking forward to greeting returning students and giving a special welcome to those of you who are on campus for the first time. We know it took a lot to get here. Have you ever wondered what it would have been like to apply to college 120 years ago? Last year we published a series of early entrance examinations from the Seven Sisters, the schools (including Bryn Mawr College) that defined prestigious women’s education in the late nineteenth century. Though the institutions were all founded with slightly varying visions, they were set apart as a group from earlier models of women’s education by their mission to provide academically rigorous schooling that led to a degree. For the first time, women were being offered an academic experience that was comparable to that enjoyed by men.1

The difficulty of getting into a good college is a constant source of discussion in the twenty-first century, with admissions departments seeing incredibly high numbers of qualified applicants every year. Shouldn’t it have been easier to get into college 150 years ago, when there were fewer people applying? Not so, as we learned in the last post: even if there were only a handful of girls around the country whose parents were interested in making sure they had access to a college education, getting in was hardly a piece of cake. As our readers noticed, the entrance exams were hard—hard enough so that few of us could pass today, perhaps even after the four-year education that the exam would have qualified us to receive!

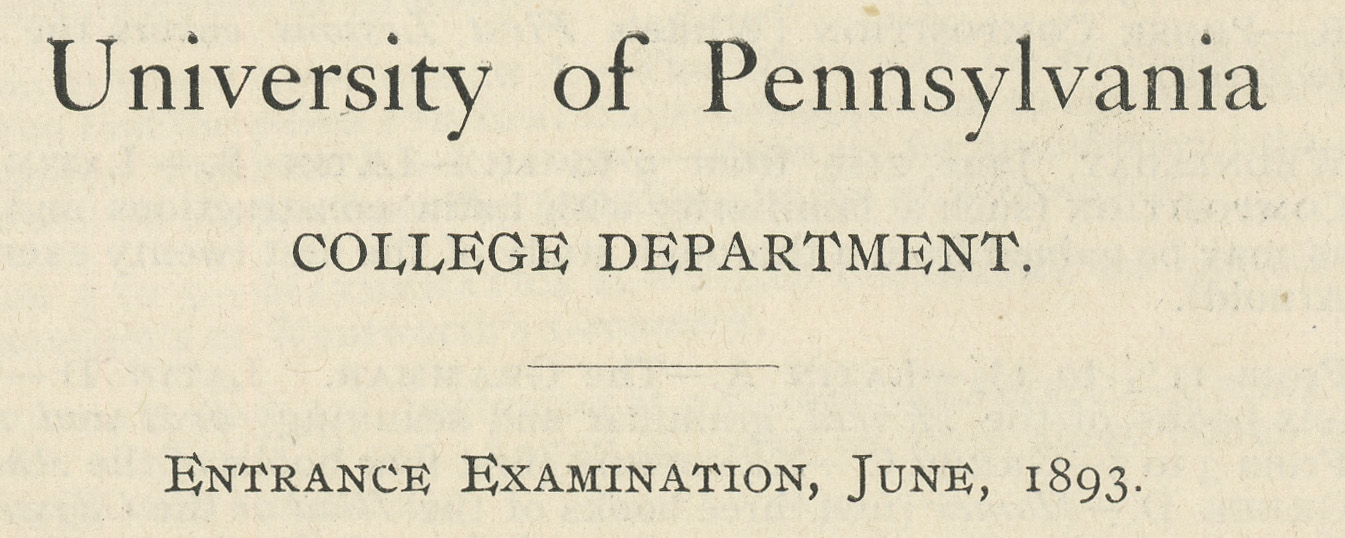

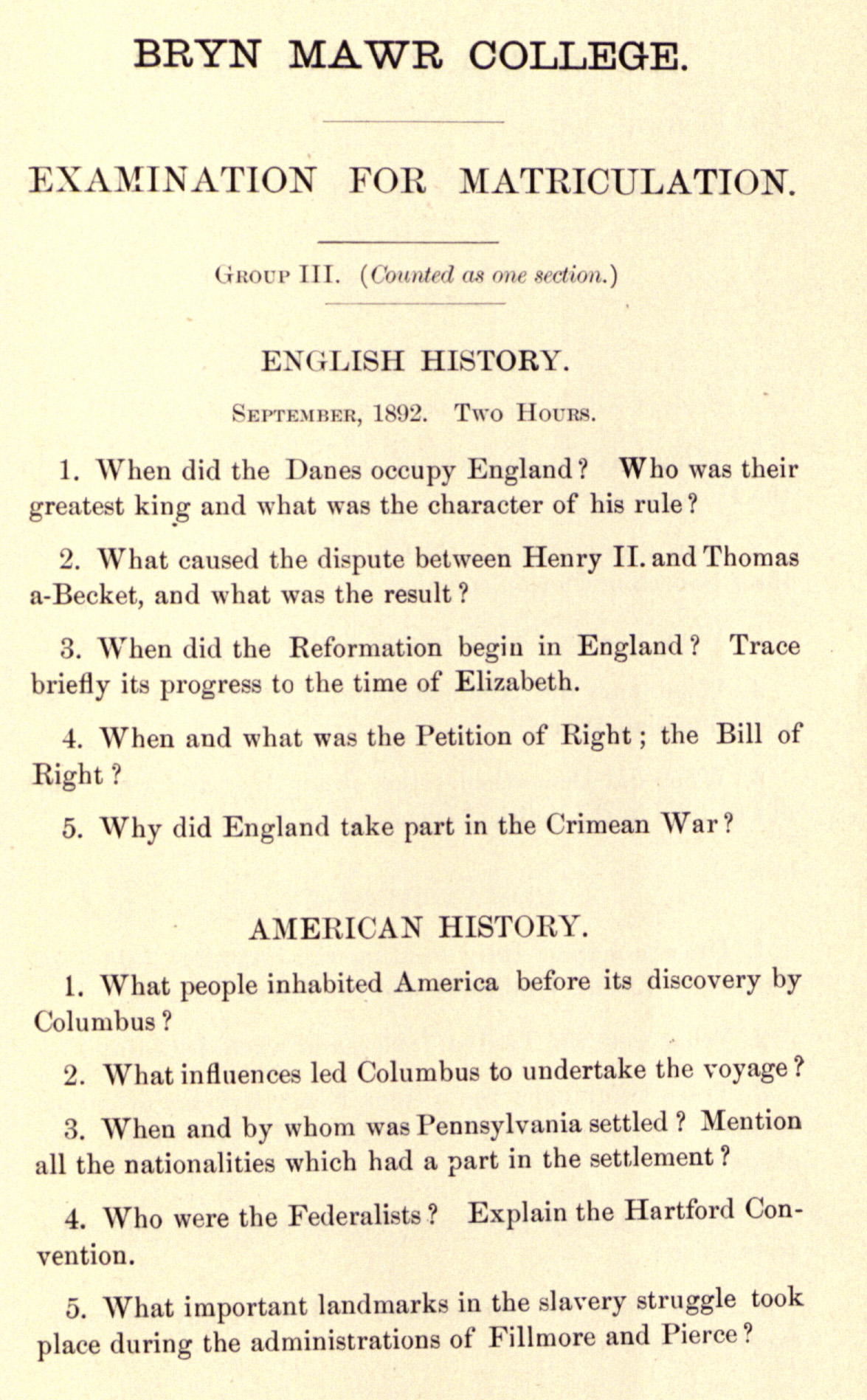

Last time we looked at how Bryn Mawr compared to the other Seven Sisters. But how would the test measure up against similar examples from the Ivy Leagues themselves? It is well documented that M. Carey Thomas, the first Dean and second President of Bryn Mawr College, aimed to make the education offered by Bryn Mawr equal in rigor to the standard American male education. Shaped by her vision, the College pursued this objective more deliberately than any of the other contemporary women’s colleges. While digging through the archives recently we came across a document describing the entrance examination for the University of Pennsylvania, as given in 1893, as well as a copy of the Harvard Examination for Women,2 also from 1893. Comparing these three documents gives us a window into how Bryn Mawr3 would have appeared alongside the schools it was designed to emulate.

The Harvard examina

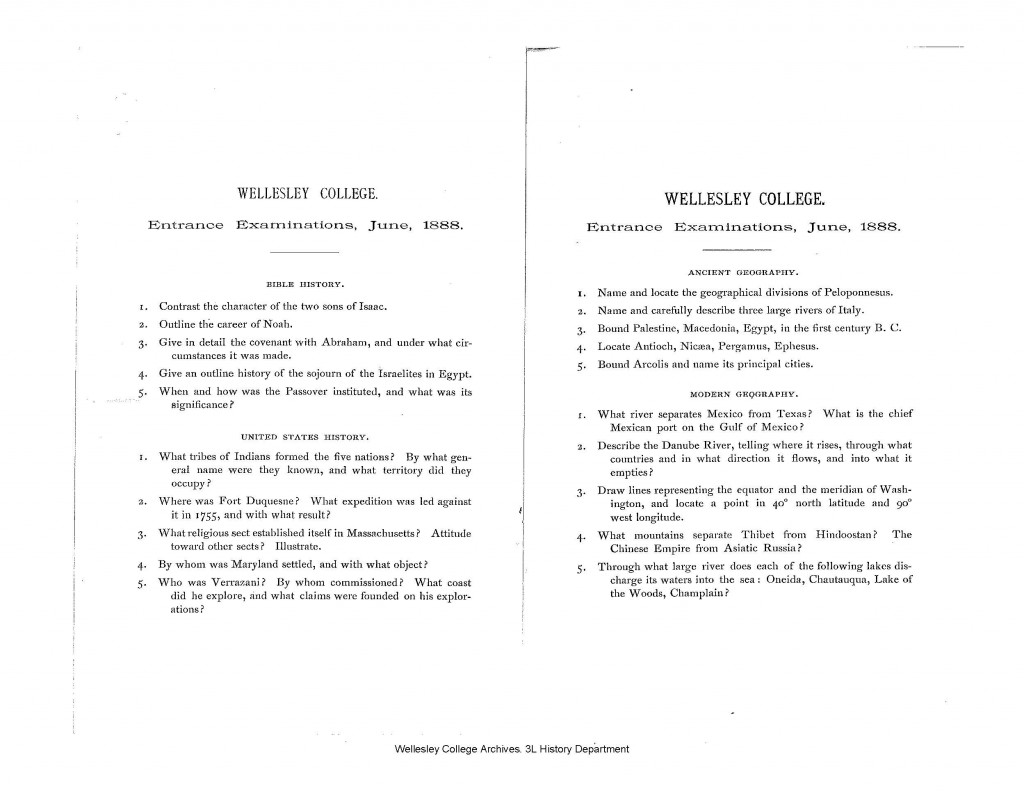

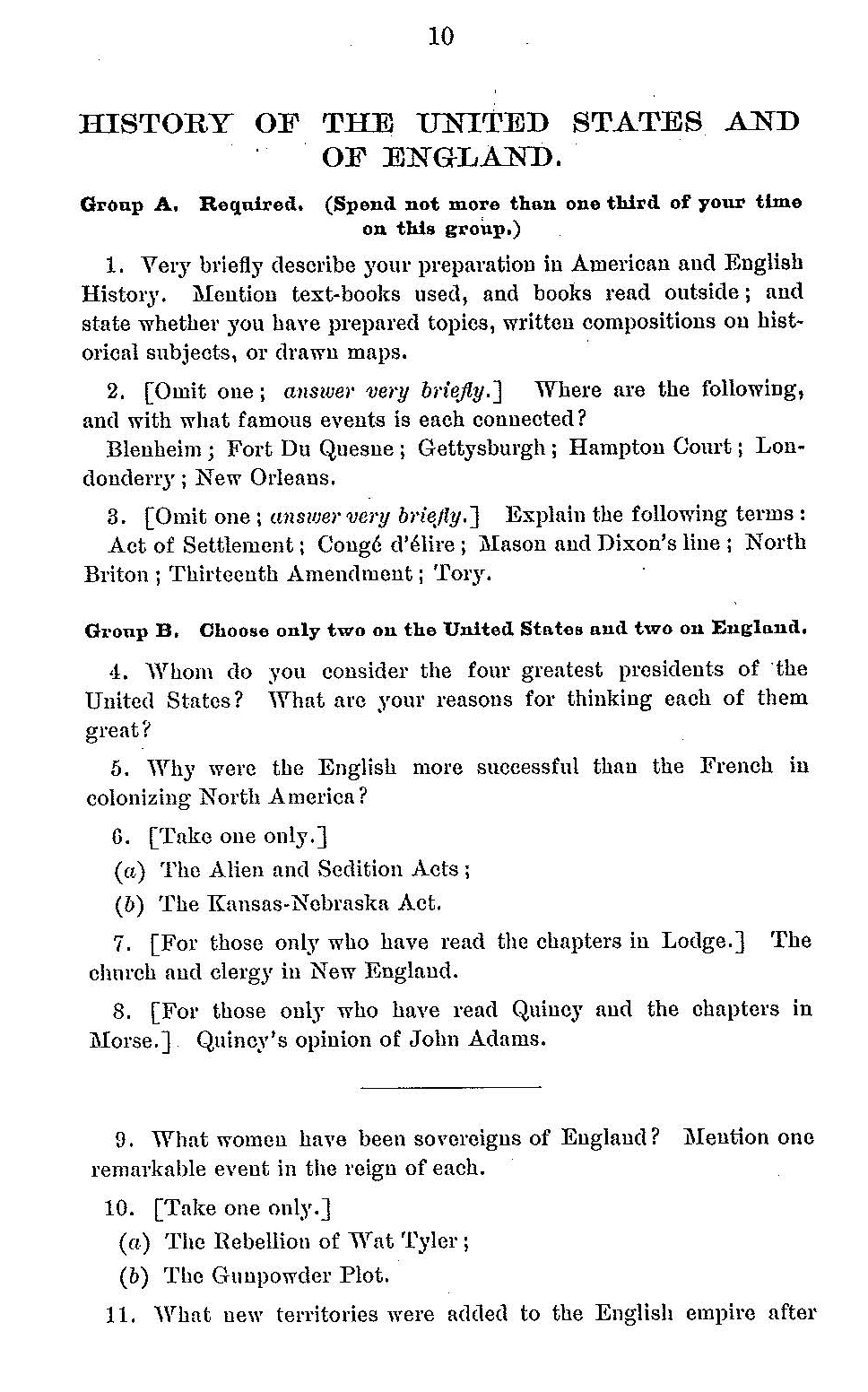

tion and the Bryn Mawr examination have similar sections in algebra (though Harvard’s has only one section, while Penn and Bryn Mawr both feature two) and geometry. All three have a heavy focus on classical studies, which were considered to be an essential area of study in history, philosophy, literature, and languages for all serious students in the nineteenth century. The first deviation that I noticed is that a scan of Harvard’s history essay questions and Bryn Mawr’s reveal a stylistic difference: while Harvard’s requires definitions of terms and summaries of events, Bryn Mawr’s essay questions tend to be more in-depth, as you can see from the pages shown above. (The Bryn Mawr exam shown to the left, Harvard on the right. Click for an enlarged view.) The subjects covered by the different exams (as far as we can tell from the documents we have access to) are as follows:

tion and the Bryn Mawr examination have similar sections in algebra (though Harvard’s has only one section, while Penn and Bryn Mawr both feature two) and geometry. All three have a heavy focus on classical studies, which were considered to be an essential area of study in history, philosophy, literature, and languages for all serious students in the nineteenth century. The first deviation that I noticed is that a scan of Harvard’s history essay questions and Bryn Mawr’s reveal a stylistic difference: while Harvard’s requires definitions of terms and summaries of events, Bryn Mawr’s essay questions tend to be more in-depth, as you can see from the pages shown above. (The Bryn Mawr exam shown to the left, Harvard on the right. Click for an enlarged view.) The subjects covered by the different exams (as far as we can tell from the documents we have access to) are as follows:

Bryn Mawr

|

University of Pennsylvania:

|

Harvard:

|

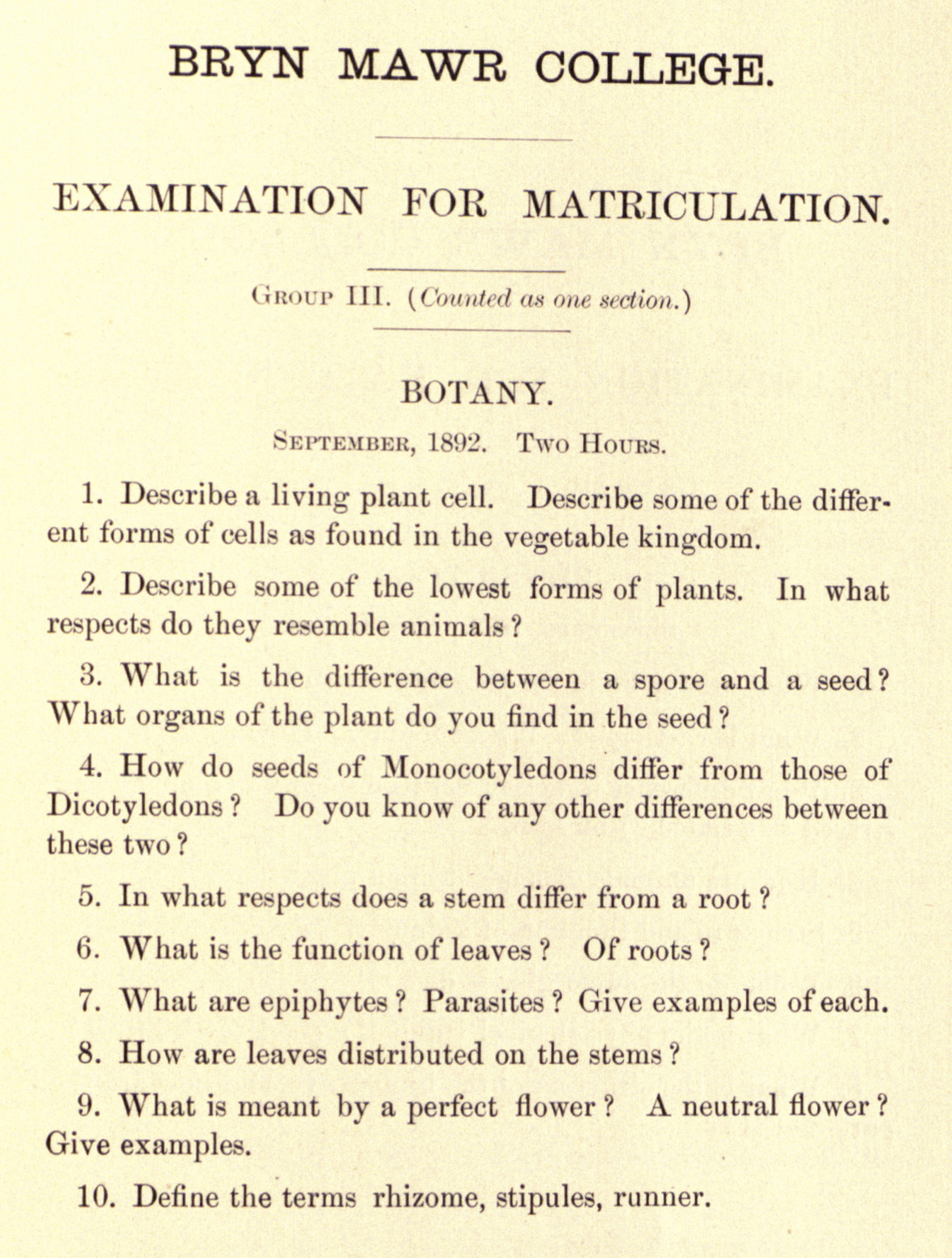

It is difficult to make direct comparisons between the Bryn Mawr examination and the other two, considering that there are portions missing from the Harvard examination, and we only have a summary and description of the University of Pennsylvania examination. The University of Pennsylvania also had different requirements based on the division of their General Course in Science from the Course in Arts, options for specialization that the other schools did not incorporate into their exams. However, given the variances, the Bryn Mawr exam appears to require a broader command of subject matter from each candidate. For example, Bryn Mawr considered language study to be of the utmost importance, and required all candidates to be tested in Latin and two languages from Greek, German, and French. If she was not examined in all four, the candidate would be required to study a fourth language as part of her college curriculum. The University of Pennsylvania requirements, however, were narrower: candidates for the Course in Arts were examined in Latin and Greek only; candidates for the General Course in Science could elect to be tested in two  languages from Latin, French, and German, and candidates for the course in engineering were only required to know one language, either German or French. By gearing the test towards specialization in either humanities or sciences, the University of Pennsylvania thus required a narrower range of material for each candidate depending on his future area of study. Even candidates not applying to a specialized course at Bryn Mawr were required to have broad knowledge of both humanities and sciences—it appears to be the only one of the three schools that included a full section on botany. Would you have passed the section on botany based on your high school education?

languages from Latin, French, and German, and candidates for the course in engineering were only required to know one language, either German or French. By gearing the test towards specialization in either humanities or sciences, the University of Pennsylvania thus required a narrower range of material for each candidate depending on his future area of study. Even candidates not applying to a specialized course at Bryn Mawr were required to have broad knowledge of both humanities and sciences—it appears to be the only one of the three schools that included a full section on botany. Would you have passed the section on botany based on your high school education?

An in-depth look at all three examinations suggests that the Bryn Mawr examination was the most challenging, mostly because of the incredible range of the subject matter in which the candidate was expected to demonstrate competence. This was directly connected to M. Carey Thomas’s vision for the type of education the school was to provide: in a published address given in 1900, entitled “College Entrance Requirements”, Thomas firmly stated her belief that “certain studies should be taken by everyone if we have in view the creation of intellectual power.” And it was the powerful intellect, not just career preparedness, that she was interested in cultivating for her students. Another reason that she advocated breadth as well as depth of study, especially in the pre-college and early college years, was that she did not believe that intellectual proclivities would necessarily arise immediately—the student needed time to explore different options and develop her abilities. In a memorable passage from the address, she refutes a statement by President Charles Eliot of Harvard University, first quoting him in his claim that “by the seventeenth, eighteenth or nineteenth year almost every peculiar mental or physical gift which by training can be made of value is already revealed to its possessor and to any observant friend” and responding that “I believe it is very rare—and as a rule profoundly unfortunate—for a decided aptitude or bent to manifest itself before a boy or girl has been two or three years in college, and usually the consciousness of it comes much later than this.” Thomas considered a broad education to be essential for the intellectual development of her students, no matter what they specialized in. However, it is also easy to imagine that the examination was crafted to be challenging in order to prove her point that women were as capable academically as men, and that Bryn Mawr College would be the school to prove that women could be educated at a level on par or even better than that of the equivalent elite male schools.

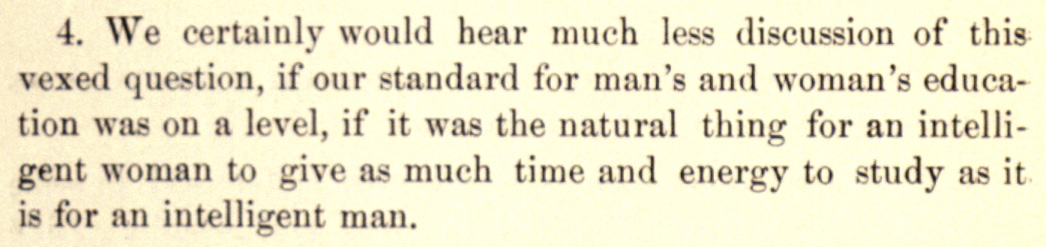

There is one item on the examination that distinguishes Bryn Mawr from its Ivy League counterparts and provides a hint as to what kind of school the candidate was applying to. In the grammatical correction section, candidates were required to fix the wording of the following passage:

Could it have been selected at random, or was it perhaps a nod of acknowledgment between the examiner and the candidates, aligned by a common conviction?

Could it have been selected at random, or was it perhaps a nod of acknowledgment between the examiner and the candidates, aligned by a common conviction?

Would you have passed the Bryn Mawr examination as given in 1893? Would you have preferred to take the more focused University of Pennsylvania exam, or the Harvard Examination for Women? Do you think interdisciplinary study and late specialization is an important component of the college experience? Let us know in the comments section!

To view the examinations in full, click on the following links:

- Bryn Mawr College 1892 Entrance Examination

- Harvard University Examination for Women 1893

- University of Pennsylvania Entrance Examination 1893

Footnotes

1 Furthermore, institutions like Bryn Mawr were offering access to graduate level education to women in the US, opening up the possibility of graduate study for American women without traveling to Europe for doctoral work as M. Carey Thomas had done.

2 The Harvard Examination for Women was a special case, as it was the only one that did not lead to admittance to the university issuing the test. At the time that Harvard began to give the examination, it did not admit women: the test was a way for young women to seek a certificate of academic achievement—a mark of accomplishment, rather than a ticket to the next phase of study. Though the University began offering classes to women through the Harvard Annex in 1879, it did not grant degrees to female scholars until the opening of Radcliffe College in 1894. Passage of the test was considered very prestigious, and the Bryn Mawr College entrance exam specifies that the Bryn Mawr entrance exam must be taken by all “except those who have passed in the corresponding divisions of the Harvard University Examination for Women, or who present a certificate for honorable dismissal from some college or university of acknowledged standing.”

3 We were unable to locate a Bryn Mawr College entrance examination from 1893, and will therefore be using an 1892 test for comparison.