Today’s guest blogger, Temple University student Matt Cahill, reflects on his experiences doing research at Bryn Mawr Special Collections as part of the Cultural Fieldwork Initiative organized by Greenfield Digital Center Advisory Board member and Temple University historian Christine Woyshner. We wish Matt well as he completes his studies and student teaching later this year!

Prior to this experience, I did not have much experience working in cultural institutions, beyond doing outdoor maintenance for a historic property in Haverford Township. As a result, I was excited that I was going to be spending time during my Fall semester at Bryn Mawr College Special Collections!

Since Bryn Mawr is one of the oldest women’s colleges in the country, they have a vast collection of artifacts, documents, and photos relating to the College and women’s history. I was surprised how many people entered Special Collections just to look at the archives! For example, when I attended a Personal Digital Archiving Day workshop, members of the Bryn Mawr College fencing team came wondering how they can preserve their history for future generations to study. There were also scholars from as far as England who spent time in the Special Collections reading room. Since I live by the College, I take it for granted.

I thought only very large museums and institutions [maintained] special collections. However, I realized that no matter the size of the institution, it is important to maintain collections because they provide a lens for understanding larger events or phenomena.

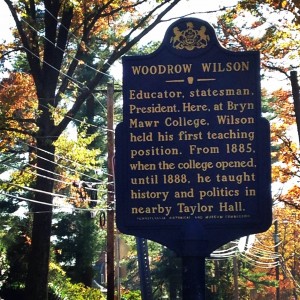

The best example of this was on my very first day, as I was finding my way to campus. At the entrance of the College’s guest parking lot, there is a historic marker about President Woodrow Wilson. Reading the marker, I found out that Wilson was the first history professor at the College in the 1880s. I lived nearby for years and never knew this! So when I started looking through Bryn Mawr Special Collections, I went straight to the collections of faculty papers. Some of the files I read included syllabi from Wilson’s classes and letters he sent. One letter I found was Wilson complaining that teaching women was below him — he did not see the point. I found this extremely interesting because Wilson later became the President about the time of the woman’s suffrage movement. By reading a letter like this, I was saw Wilson’s views of women before he became a national figure.

As part of my time at Bryn Mawr, I was asked to make a lesson plan for the Greenfield Digital Center’s collection of classroom materials designed by Temple secondary education students, making Special Collections usable for teachers and students. When I heard about my assignment, I knew that I wanted to center my lesson on Woodrow Wilson and Bryn Mawr. I thought that it would be a good lesson because local teachers can fit it right into a unit on World War I or woman suffrage.

Once I had a lesson topic, I needed to start crafting it into a workable lesson. The first thing I did was create a bibliography. Even though the focus of the lesson was Wilson’s letter, I wanted to add some more useful sources that a teacher might want to use. For example, I included two academic articles that show the different sides of the Wilson’s view of women. In addition, I included a section of a letter that Wilson’s wife wrote to him complaining that teaching at Bryn Mawr was below him. By doing so, I suggested documents to teachers that they can use to expand the lesson or student’s interest in the topic.

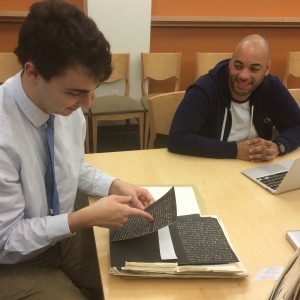

Temple University students Matt Cahill and David Polanco compare findings in the Special Collections seminar room, November 2014.

When I started crafting my lesson, I had free range to write it. At first, I was afraid that I would have to follow a specific format but that was not the case. Greenfield Center Director Monica Mercado encouraged me to write the lesson the way I would teach it as a future instructor. I think the reason for this encouragement was that she knew if I were really into the lesson than other teachers would be excited about it and will use this lesson and others. When I looked at other cultural institutions’ lesson plans they were rigid and conformed around one teaching style. As a result it makes the great primary sources they provide not that inviting for teachers. Cultural institutions want teachers to use their primary sources. However unless the teacher has some freedom then they will continue using the textbook for the majority of the time.

I decided that I would have my lesson be discussion based. The reason is that I think it is the most effective when students read and discuss primary sources with their classmates. By doing so, students can develop a better understanding of the text by listening to the insights from others. Also it brings history to life for students because they are not seeing Wilson as just this figure in a textbook but someone who lived and worked in the area.

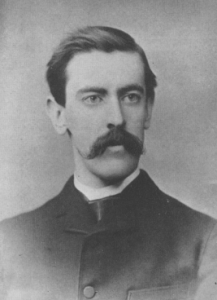

Woodrow Wilson at the time of hist teaching appointment, portrait reproduced in the Bryn Mawr Alumnae Bulletin (1955).

For the organization of this lesson, students first share everything they have learned about Wilson. After that the teacher introduces the students to the historical marker by Bryn Mawr College, and then the teacher has students read and discuss Wilson’s letter complaining about woman’s education. After reading the letter, the teacher will ask the student’s about the thoughts and reaction Wilson’s letter. Some of the other questions include having the students discuss the meaning of having this marker near Bryn Mawr despite Wilson’s strong feelings against woman’s education. As a result, students see that not everything they read or see in the world around them should be judged on face value. At the moment the assessment I suggested is for students to decide if and how they would change the historic marker based on the information during the discussion. For homework, students will rewrite the marker and write a paragraph or two on why they would change it.

[The lesson plan is now online, here.]

The biggest take away from my time at Bryn Mawr is that primary sources are best used when there is a lot of freedom for the teacher and students. The great thing about primary sources is that they are open and can be looked at in multiple ways.