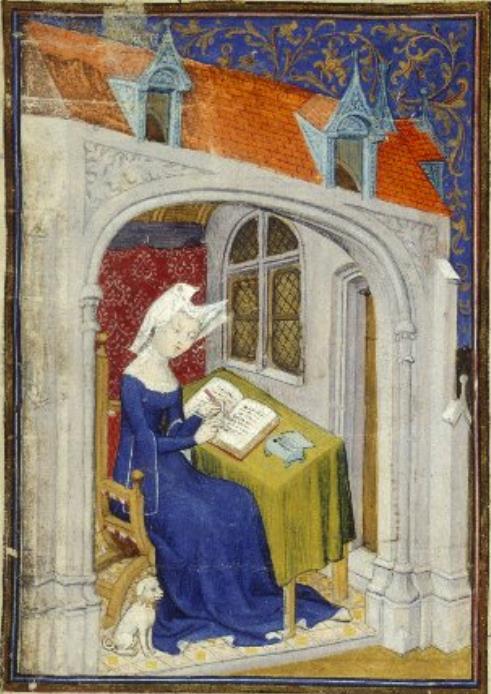

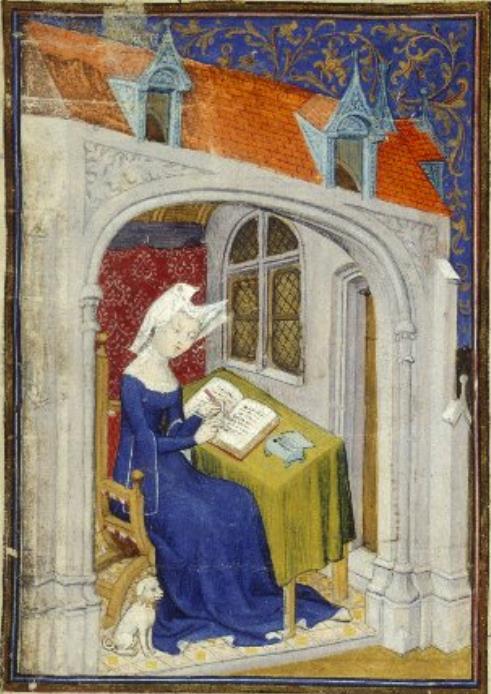

Christine de Pizan

In this guest post, Elena Johnson ’16 reflects on architecture, female scholars, and intellectual inspiration. In the Balch seminar, ‘Bookmarks‘, Professor Katherine Rowe asks her students to consider the tools and conditions that shape the way we think and write. Drawing inspiration from a syllabus that included Virginia Woolf and Christine de Pizan, among others, Elena began to theorize the role of the constructed academic environment in which she found herself during her first year here at Bryn Mawr. This essay is her reflection on windows–both as a source of inspiration and illumination, and as a representation of the spatial luxury to which not all female scholars have had access.

Elena collaborated with the Albert M. Greenfield Digital Center for the History of Women’s Education to pair her words with photographs from the Bryn Mawr College archives, which illustrate some of the themes that weave throughout the piece. In addition to appearing in this post, we will be releasing weekly clusters of images on our Tumblr page. Be sure to follow us so that you don’t miss any! And check out the first posting here.

…

Bryn Mawr rises from a foundation of scholarly pride and ambition. Rather than model its dorms and classrooms after other women’s colleges, it takes its inspiration from the brooding gothic edifices of Oxford and Cambridge. Stone worked like lace glitters with windows in a statement of almost overwhelming grandeur: this is not Virginia Woolf’s impoverished Fernham1. Its founders did not intend for it to serve as a home away from home, with all the “women’s work” that that then implied, but as a rigorous monument to academia. If nothing else, it does its best to intimidate newcomers.

Virginia Woolf

As a freshman at Bryn Mawr, I enrolled in the school’s writing seminar program. Instead of reading about volcanoes or Greek mythology (my other two choices), I found myself in a class called ‘Bookmarks’, where we read Christine de Pizan and Virginia Woolf2. Both women published their work in times and places where female scholars were relatively rare and considered something of a joke at best. Both took on the challenge of defending women, but where Christine claimed the existence of an innate feminine virtue, Woolf declared that women had been deprived of the basic essentials requisite to great writing. It was while reading these, surrounded by echoes of Oxford and Cambridge, that I realized the subject for this essay: windows.

In her essay, A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf proposes that by possessing both a private room and the money to pay for a comfortable life, a writer gains independence: the ability to separate oneself from the bitterness and distraction of reality. But in isolating these prerequisites to genius, Woolf overlooks a third, equally vital resource. Windows provide the writer with light, a view, and a degree of isolation somewhere between mind-numbing loneliness and the constant interruptions of the wider world.

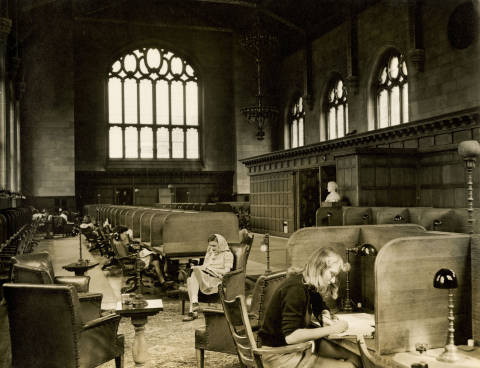

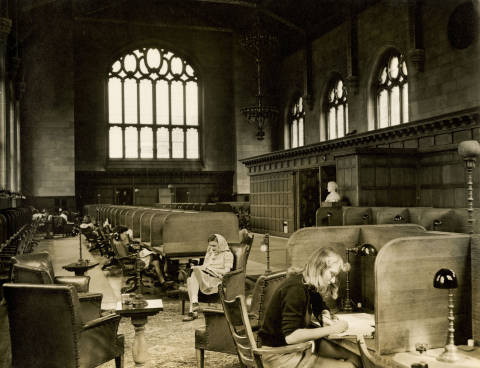

Thomas Library

Traditionally, windows address a practical concern by providing would-be scholars with the light they need to work. At Bryn Mawr, they grace the high walls of Thomas Great Hall, once the reading room of Bryn Mawr’s library, with gothic splendor. In this photo, lamps sprout from every desk, yet the students pictured work mainly by the natural light that floods the room. Today, the Canaday, Collier and Carpenter libraries have replaced Thomas as popular study spots, but if anything these modern equivalents have expanded on its window-laced walls and the students who study in their sunlit carrels draw easy comparison to a much older variant on the same theme.

Christine de Pizan

In illustrations of The Book of the City of Ladies, Christine appears illuminated by windows. One artist includes skylights and a wide arced opening, which take advantage of the sunny day (see image at top of post), while another demonstrates the aid these windows lend with a handful of long golden rays cast over the writer and her desk, highlighting her work in the eyes of the viewer. Writing in a room of her own, with sufficient funds, with the light provided by her windows, Christine produced valuable volumes to help fill the sorry gap on Woolf’s shelf.

Windows offer metaphorical illumination in addition to the more practical sort. In A Room of One’s Own, Woolf describes the “branch of illumination” (Woolf 44) and the “lamp in the spine” (18) as the source of brilliance and innovation, while spending bright sunny afternoons at the imaginary Oxbridge as she searches for inspiration. However, the real world thwarts these sources: the Spartan meal at Fernham puts out the lamp, and outraged gentlemen cast shadows on her day at Oxbridge. Both the light and Woolf’s inspiration, linked in her mind and in her words, are disrupted by the realities of sexism. Only in the final scenes of her essay, as Woolf awakes to “the light . . . falling in dusty shafts through the uncurtained windows” (94), does the “branch of illumination” bear fruit, drawing her away from the looping and frustrated logic of a male-dominated world and allowing her to think, clearly and independently, in her own room, with her own money.

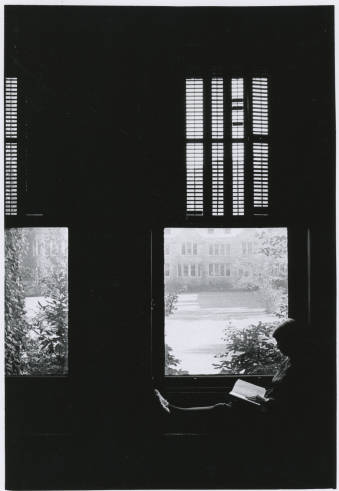

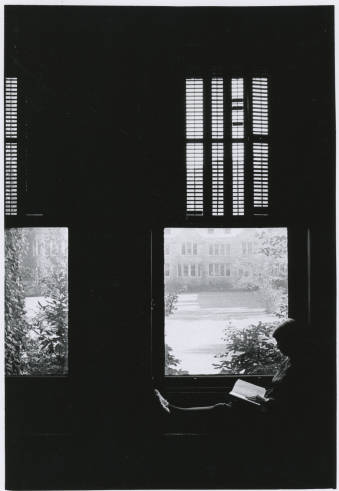

Studying in a window

Where light mingles physical necessity with a more esoteric need, the view through a window exists more basically as a source of inspiration. Woolf benefits from this phenomenon throughout her struggle to produce A Room of One’s Own. First, at Oxbridge, the sight of a tailless cat through the window inspires Woolf to ponder the missing elements in a society torn by post-war sexism. Then at Fernham, she and Mary Seton discuss the poverty of their sex while standing at a window overlooking the grandeur of Oxbridge. However, Woolf’s greatest revelation occurs at the window of her private rooms in London. Exhausted after struggling through the male-dominated shelves of the library without much success, Woolf finds her answers through her bedroom window, where the sight of a man and a woman climbing into a taxi together finally inspires the conclusion of her essay.

Just as a window lets light in, it keeps out a world of interruptions, creating a degree of separation that allows Woolf to enjoy the isolation of her room without sacrificing the benefits of a broader view. While walking over the fields of the fictionalized Oxbridge, Woolf suffers constant interruptions that repeatedly destroy her thought process. Only by imagining herself “contained in a miraculous glass cabinet through which no sound [can] penetrate” (6) can Woolf resume thinking, albeit temporarily, glorying in her “freedom from any contact with the facts” (6). This early realization later contributes to Woolf’s high regard for privacy, but the mention of glass bears scrutinizing. While walling herself off from the facts of an oppressively sexist society gives her room to think, Woolf thinks about what she sees, inspired by the world around her. Though this paradox has no easy solution, windows appear as a possible compromise.

The degree of separation a window offers also gives refuge to the “androgynous mind” as Woolf calls it, referring to Coleridge. She posits that because of the recent polarization of the sexes, the works her contemporaries produce lack the same element of suggestion present in Coleridge, Shakespeare and Austen. Writers become too obsessed with defending or injuring one sex or the other, personifying masculinity or representing femininity. The window allows the writer’s mind to “separate itself from the people in the street” (96) and the emotional and cultural turbulence inherent there. A writer at a window need not write as a man or a woman about men or women, but as a person about people. Whether sitting by a  window in a London apartment, or in a dorm in Bryn Mawr, or in a medieval study while dreaming of a City of Ladies, the presence of windows offers the same thing: a degree of isolation between you and yourself, a space to see society without getting caught up in its emotion, and an unparalleled opportunity for authenticity without interference.

window in a London apartment, or in a dorm in Bryn Mawr, or in a medieval study while dreaming of a City of Ladies, the presence of windows offers the same thing: a degree of isolation between you and yourself, a space to see society without getting caught up in its emotion, and an unparalleled opportunity for authenticity without interference.

A room of one’s own means a door with which to lock out the skeptics and critics, even the simple doubters who smile condescendingly at the writer’s hunger for self-expression. That five-hundred a year, now a much larger sum, means the writer need not depend upon a skeptical father, or a critical husband, or a doubtful boss for her livelihood. While privacy and independence help, the writer will also need a window. Not necessarily a very great window or a very beautiful one, but a gap in the wall through which light may enter in and her mind may wander out, free from scrutiny. A window, so that when she pauses, grasping at the next thought to put on paper, she may see beyond her room and her money and the waiting page. Perhaps she will see nothing but the cold rain, tapping against the glass and forming clear rivulets that pool in the grass. Or, maybe, she will see two people, a young woman and a young man, get into a taxicab together and drive away.

Do you have a favorite window on campus? Do you prefer to work by natural light, or in a more secluded environment? Respond in the comments, or tweet your replies @GreenfieldHWE.

Editorial assistance by Evan McGonagill.

Footnotes

1. In her essay, Woolf juxtaposes the impoverished, fictionalized women’s college “Fernham” with the wealthier, equally fictionalized men’s college “Oxbridge” in an effort to highlight the disparity between the sexes, as well as the positive effect luxury has on innovative thought.

2. Because of the naming conventions of the era, scholars refer to Christine by her first name only. So for the sake of accuracy (and at the cost of comfort) I will do the same in this essay.

![]() Home is a natural place of belonging. However, as a threshold between the politics of domesticity and ideologies of nationhood and citizenship, it proves a loaded construct within the production of space. Read in tension with issues of migrations, ‘home’ becomes further charged. Such themes (considered, for example, in the work of Mieke Bal) have provided rich material worked by female artists in particular, addressing and challenging homes and homelands, their comforts and their strictures. 20th and 21st-century migrations, those of enforced mobility (expulsions) or performing the agency of motility (emigrations, whether on the domestic or the transnational level), have further destabilised previous concepts of ‘home’. Is home now a lost space? And, if so, how might, or have, artworks navigate(d) the precarious terrains of nostalgia such a loss makes present? Can practices of emplacement compensate for the absence of home? Can ‘home’ be reconstructed, perhaps even contesting nationalisms? Can memories function as operational tools re-mapping ‘home’ and emancipatory narratives?

Home is a natural place of belonging. However, as a threshold between the politics of domesticity and ideologies of nationhood and citizenship, it proves a loaded construct within the production of space. Read in tension with issues of migrations, ‘home’ becomes further charged. Such themes (considered, for example, in the work of Mieke Bal) have provided rich material worked by female artists in particular, addressing and challenging homes and homelands, their comforts and their strictures. 20th and 21st-century migrations, those of enforced mobility (expulsions) or performing the agency of motility (emigrations, whether on the domestic or the transnational level), have further destabilised previous concepts of ‘home’. Is home now a lost space? And, if so, how might, or have, artworks navigate(d) the precarious terrains of nostalgia such a loss makes present? Can practices of emplacement compensate for the absence of home? Can ‘home’ be reconstructed, perhaps even contesting nationalisms? Can memories function as operational tools re-mapping ‘home’ and emancipatory narratives?