As part of our celebration of Women’s History Month, The Albert M. Greenfield Digital Center for the History of Women’s Education is featuring content from The Woman’s Column, a pro-suffrage publication that ran from 1887 through 1905. We have been posting weekly blog entries that feature individual articles from the Column that were published in the month of March and address the matter of women’s higher education, although the publication addresses many other issues related to women’s rights and their access to political life and the public sphere. This post is the fourth and final installment in the series; see our first, second, and third posts to learn more.

As part of our celebration of Women’s History Month, The Albert M. Greenfield Digital Center for the History of Women’s Education is featuring content from The Woman’s Column, a pro-suffrage publication that ran from 1887 through 1905. We have been posting weekly blog entries that feature individual articles from the Column that were published in the month of March and address the matter of women’s higher education, although the publication addresses many other issues related to women’s rights and their access to political life and the public sphere. This post is the fourth and final installment in the series; see our first, second, and third posts to learn more.

In addition to changes in policy at American universities, The Woman’s Column chronicled the state of women’s higher education abroad. Not purely for the globally-minded, such information would have been personally relevant to many American ladies: though the establishment of the women’s colleges known as the Seven Sisters had made the BA much more accessible to academically ambitious girls, more advanced degrees were difficult to obtain within the country. Bryn Mawr, which launched in 1885, was the only women’s college to open with a full graduate program. Several coeducational schools offered examinations and tutelage for female students, but were unwilling to confer an official degree, such as Harvard University. Europe, however, became an attractive option for graduate study, housing as it did centuries old universities that offered an array of graduate training. Travel to Europe was also an opportunity to broaden one’s cultural horizons, to see famous monuments, meet important scholars of the day, and to round out an American education that for many readers, may have consisted solely of single-sex environments in sheltered campuses across the country.

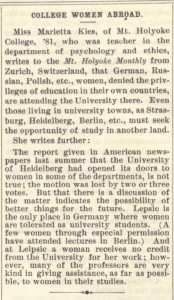

A report from an alumna and former teacher at Mount Holyoke College was published in The Woman’s Column on March 11, 1893, stating: “German, Russian, Polish, etc., women, denied the privileges of education in their own countries, are attending the University [of Zurich].” “Lepsic [sic] [Leipzig],” she writes, “is the only place in Germany where women are tolerated as university students….And at Leipsic a woman receives no credit from the University for her work; however, many of the professors are very kind in giving assistance, as far as possible, to women in their studies.”

For those familiar with the early history of Bryn Mawr College, much of this will sound familiar. M. Carey Thomas, the school’s first Dean and second President, followed a complex path through several universities before eventually earning her Ph.D. summa cum laude in linguistics from the University of Zurich. After receiving her undergraduate degree from Cornell, she attended Johns Hopkins University for a single year before departing, frustrated: though she was allowed to study with professors and sit for examinations, she was not permitted to attend classes and therefore found the experience challenging and inadequate. Given the dearth of American schools that allowed women to attend classes with men, she saw the European universities as her only path to a graduate degree. She went on to complete the bulk of her literary work at the University of Leipzig with the knowledge that such study could be only preparatory–for, while the lectures were open to her, Leipzig did not grant degrees to women. Gottingen University, however, seemed to operate with reverse policies: women could not attend classes, but there was no official rule prohibiting them from receiving degrees. Once she had taken her studies as far as she could at Leipzig, she transferred to Gottingen to complete the final hurdle to the doctorate. However, despite the lack of a formal ban, she learned after preparing her dissertation that the all-male faculty had voted not to grant her the doctorate on the grounds of her gender. Thomas, indefatigable, moved on to the University of Zurich, where she successfully prepared, presented, and defended the thesis that finally earned her the Ph.D. she had long sought. Thomas’s convoluted path shows the difficulty, not to mention the required time and financial resources, that stood in the way of the American woman intent on a doctoral degree.1

As we have previously discussed on this blog and in our exhibits, there were many well-documented arguments about why to keep women out of the educational system altogether. Aside from doubts about women’s inherent ineducability, many argued against coeducation for social reasons. For instance, Harvard President Charles Eliot cautioned that coeducation in urban schools could lead to dangerous class mixing and undesirable marriages, as we have previously discussed. But what was the logic of letting them study among men while refusing them the qualification that they had earned by it? Oxford University provides an interesting case that can help us understand the terms of the debate.

A March 28th, 1896 article in The Woman’s Column entitled “Oxford Not Ready” recounts the University’s decision to reject a proposal to open the BA to women. Many female students were already completing the work that would have qualified a man for the degree, much in the style that Leipzig had made its coursework but not its official recognition of achievement available to women. The Oxford motion was struck down by 75 votes, 215 vs. 140. The leader of the opposition, Mr. Strachan Davidson, held that “the life [at Oxford and Cambridge] stamped a special character on the man, and it was to that that the B. A. certified. Examinations were only secondary, but the degree testified to the man’s career as a whole. The women could participate in the examinations, but not in the life. He did not wish to say one word hostile to the ladies’ colleges, but the life there was not a University life.”

A March 28th, 1896 article in The Woman’s Column entitled “Oxford Not Ready” recounts the University’s decision to reject a proposal to open the BA to women. Many female students were already completing the work that would have qualified a man for the degree, much in the style that Leipzig had made its coursework but not its official recognition of achievement available to women. The Oxford motion was struck down by 75 votes, 215 vs. 140. The leader of the opposition, Mr. Strachan Davidson, held that “the life [at Oxford and Cambridge] stamped a special character on the man, and it was to that that the B. A. certified. Examinations were only secondary, but the degree testified to the man’s career as a whole. The women could participate in the examinations, but not in the life. He did not wish to say one word hostile to the ladies’ colleges, but the life there was not a University life.”

We have spent more time previously discussing societal opposition to women’s education that centered around the female body and the importance of her traditional role in the home. However, another important factor was that the established institutions were having trouble imagining where women would fit into the existing culture of higher education, as indicated in the critique of Davidson at Oxford above; gender appeared to be a barrier to the immersion in campus life. Assuming that women could be educated at all, the issue remained that the degree had come to stand for much more than academic achievement alone: it was the mark of induction into a culture, mutually constitutive with the identity of the elite society gentleman.2 Improving women’s access to higher education was not just a matter of opening doors, as it turned out, but a matter of re-imagining the spaces themselves.

The article ends on an optimistic note:

“Of course it is only a question of time when this decision will be reversed. Conservatism thaws slowly, but it thaws surely. Meanwhile the women will have the scholarship for which a degree should stand, if they have not the degree; and they can comfort themselves by thinking,

It is not to be destitute

To have the thing without the name”

1. The educational path of M. Carey Thomas is charted in detail in her biography by Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz. See Horowitz, Helen Lefkowitz. The Power and Passion of M. Carey Thomas. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1984.

2. For a thorough exploration of the culture of masculinity of Oxbridge, see Oxbridge Men. Deslandes, Paul R. Oxbridge Men: British Masculinity and the Undergraduate Experience, 1850-1920. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2005.