Scrapbooks and photo albums present unique challenges, both to the archivist and to the historian. Scrapbooks and photo albums can be both bulky and fragile, and are composed of a variety of materials, some of which are more archivally sound than others. The objects placed in a scrapbook weaken the binding, which can cause pages to become loose, lost, or damaged. Acidic paper is typical of scrapbooks and photo albums, discoloring photographs and rendering the pages brittle. Adhesives often degrade over time, and may damage items they attach. The preservation challenges of scrapbooks and photo albums are considerable, yet “it is important for the archivist to arrange the scrapbook as an intact whole in order to retain its value” (Brunig 8). Digitization aids researchers and allows multiple researchers to utilize the objects without handling them – but on the other hand, the process of digitization requires handling of the item.

For the historian, simply accessing scrapbooks and photo albums can pose a challenge. Many remain in private hands, and those which are in archival collections may be difficult to locate and are likely to lack contextualizing documentation – frequently, the name of the compiler is not known and usually it is unclear whether the photographer and compiler were the same person (Motz 66-67). And that is only the start of the interpretative difficulties (Ott et al., Whalen, Langford 3-21).

Nevertheless, the effort to interpret these items can be very worthwhile. The Bryn Mawr College Scrapbook and Photo Album Collection provides glimpses into student life in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries which administrative records don’t, and potentially provide a powerful complement to student publications, letters, and diaries. “Photographs do not merely reproduce reality: the photographer selects a limited scope of vision, chooses a subject, and often arranges poses, props, and clothing. The compiler of an album, in turn, selects photographs for inclusion, comments on them in captions, and juxtaposes them so that the interaction of the photographs on the page and the sequence of the pages in the album become part of the message. Photograph albums therefore present a highly selective view of their subjects … Photographs present an interpretation of events” (Motz 65-66). The scrapbooks and photo albums communicate the students’ interpretation of their college experience, through images, ephemera, and sometimes even words.

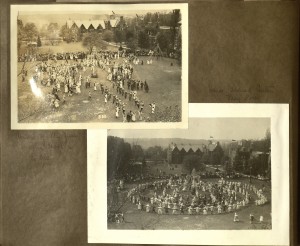

The items in the collection tend to picture highlights of student life, such as theatrical performances and May Day celebrations, two of the most commonly occurring photographic subjects – the quotidian college experience is often elusive. The candid portraits are often delightful, but without contextual written information, the difficulties of interpretation are tremendous. As Langford suggests, “our photographic memories are nested in a performative oral tradition”: scrapbooks were intended for private use, not public consumption, and in many cases would have been used as an aid to memory for an individual, or an individual’s story-telling to family members and friends (Langford viii). I recall a recent occasion when a friend showed me a video of an important event she participated in, and how her accompanying oral narration completely changed my understanding of and attitude toward the material – if anything, this experience provides a measure of how impossible it is to view photo albums and scrapbooks as they were viewed by the compilers and those close to them.

Identity and Nostalgia

There is no formula for interpreting scrapbooks and photo albums. Different interpretative methods depend, for example, on how much contextual information is available for a particular item. In the case of the Bryn Mawr College Scrapbook and Photo Album Collection, over one hundred items may be read in juxtaposition to each other. Taken as a whole, the collection reveals some important things about general campus culture. For instance, college buildings are generally a well-represented photographic subject, occurring at significant points in the visual narrative of photo albums and scrapbooks. The second page of the Photo Album of Elizabeth Holliday Hitz ’16 begins a series of photographs of Bryn Mawr College’s campus, beginning with Pembroke Arch and Rockefeller Arch, the two primary entrances (below).

Elizabeth establishes almost immediately that the material college is significant to her memories, or the memories she wishes to have, of Bryn Mawr College and her time there. But what do these buildings and spaces mean to her, and to all the other students who made sure to include images of their college’s campus?

Paul R. Deslandes describes how Oxbridge students, from 1850 to 1920, constructed their common identity as college men in part through their occupation and intimate knowledge of the restricted spaces of their university. This familiarity is, in their own view, what set them apart from other, lesser beings, including female relatives, foreigners, and people of lower classes (Deslandes 29-33). The material college was linked to a collective undergraduate sense of self, and sense of superiority as upper-class Protestant white English men. Additionally, “the student was expected to establish deeply rooted emotional attachments to the university that were permanent, not fleeting. The memories that college life fostered … were frequently described, in a world preoccupied with delineating the boundaries separating insiders from outsiders, as enduring marks of status” (Deslandes 27). For Oxbridge undergraduates, identity, nostalgic memories, and status were all linked to the buildings and spaces of their university.

Possibly Bryn Mawr College’s campus had a similar link with identity, memory, and status for its students. M. Carey Thomas intended the campus to physically recreate the great universities of Europe, and to provide an appropriate space for the life of the mind. However, as Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz explains, before long “students subverted the entire campus into a great stage setting for ‘the life’ [as student campus culture was referred to]” (Horowitz 170). The campus was the backdrop not only to their studies but also to their informal socializing and athletic competitions, their banquets and theatrical productions. “With the growth of rituals the campus assumed a new importance as a ceremonial space … Many of the rituals linked the students to the college landscape” (Horowitz 174). The photographs of May Day celebrations, in the middle of campus and visually framed by college buildings, from the Scrapbook of an Unidentified Student, ca. 1922, (above) provide an example.

Horowitz cites an unnamed Bryn Mawr alumna quoted in a Radcliffe publication:

A stranger to the handsome campus might be struck by ‘the grand old stone buildings covered with ivy, by the campus stretching far off into the distance, and by the great spreading trees.’ As impressive as the scene appeared, ‘how much more then must it mean to those who have lived in those halls, studied in the library under those trees, and discussed the problems of life, death and eternity in the Cloisters … Each room, each tree, almost each corner is bound up with some special memory.’ (Horowitz 175)

Although the culture of elite white English men’s educational institutions had significant differences from college life as created and experienced by white primarily middle-class American women at women’s colleges in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it’s possible that Mawrters not only shared nostalgia with Oxbridge men of the same era for the physical spaces of their undergraduate years, but also a sense of superior, insider status. If identity and status were linked to memories of Bryn Mawr College as a place, this would explain why the compilers of scrapbooks and photo albums so often chose to include photographs of college buildings.

There is at least one alternative or additional interpretation. Marilyn F. Motz describes how

in the mid-nineteenth century, many women separated by westward migration lamented that they could not visualize the homes of those who had gone west. Women’s letters to female relatives during the nineteenth century often described house plans, wallpaper, dress fabric, and paint colors … Women frequently exchanged bits of fabric from dresses they were making and scraps of wallpaper from their houses to enable relatives and friends to form visual images of their new surroundings. The camera enabled women to reproduce these features accurately, so that friends and relatives, or they themselves at a later date, could picture the domestic environment that was so important to their identities. Many photographs … are of interior scenes, of empty rooms or people in their houses. (Whalen 72)

Gladys Stout Bowler combined photos of her dorm room with shots of Pembroke Arch and the Cloisters on one page.

Bryn Mawr students do include photographs of their dorm rooms, but only very occasionally. However, what I mean to suggest is that these college women were influenced by a tradition of women documenting their domestic surroundings. It’s true that the experience of Bryn Mawr College was not a domestic one. M. Carey Thomas strove to create an environment appropriate for serious study, not one that reproduced the middle-class home on a larger scale, and student culture broke the mold of feminine domesticity. Still, like middle-class women in traditional domestic environments, Bryn Mawr students “assembled images of their … friends and environments, symbolically placing their own lives in a context of people and places” (Whalen 73). I see a similarity in these urges to record quotidian surroundings – be they the rooms of a private home or the Collegiate Gothic architecture Bryn Mawr College’s dormitories, library, and other buildings – for the sake of absent friends and relatives, and their own future selves. In the above page of her photo album, Gladys Stout Bowler mixes photos of her dorm room with exterior shots of campus buildings, suggesting thematic similarities. My conjecture is that Bryn Mawr students adopted formats common to white middle-class American women – the photo album and the scrapbook – but the content of their creations was uniquely determined by college life. Comparisons with a body of scrapbooks and photo albums compiled by young women of similar backgrounds who did not attend college would be very informative.

Comparisons and Absences

The distinctive qualities of a particular scrapbook or photo album, or of a particular collection, emerge through comparisons. For example, I only began speculating on the importance of Bryn Mawr’s campus to student identity when I read a preliminary analysis of a scrapbook collection, dating to the early twentieth century, from Newcomb College of Tulane University (Brulig). The most common photographic subject in this collection is, unsurprisingly, people, a trait shared by many items in the Bryn Mawr College collection. Brulig’s article notes that “there was a marked decrease in the number of photographs of campus locations after 1917, which corresponds with the move to the Broadway Avenue campus in 1918” (Brunig 5). Clearly, some campuses have more of an impact than others. I’m curious about the role the material college plays in photo albums and scrapbooks made by students at the other Seven Sisters colleges, by women at co-educational institutions, and so forth. Another possibility for comparison is the family photo album. Family albums were a major genre of photo album which the compilers of the Bryn Mawr collection were certainly aware of. How did awareness of the conventions of this genre shape the photographs which Bryn Mawr students took, and the choice of which photographs to include in their albums and scrapbooks?

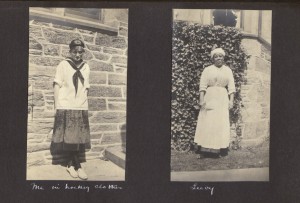

The right-hand caption reads "me in hockey clothes" and the left-hand caption names the African-American maid pictured as "Lucy".

What the students chose to leave out is as interesting as what is put in. Bryn Mawr College students in the era covered by the collection had daily contact with the African-American maids and porters employed at the college. However, when I surveyed the collection at the beginning of the digitization process, I found perhaps three or four images of African-American college employees in the entire collection. Professors comprise another neglected photographic subject. What do their choices of photographic subjects tell us about the students’ understanding of their college experience and their relationships with faculty? Or about their perceptions of race and social class, and their relationships with African-American staff? In a unique juxtaposition, above, Ida W. Pritchett ’14 places her own portrait next to that of an African-American maid. What drove Ida’s unusual choice of subject, and her decision to include it in her photo album?

Also notable is the lack of male suitors appearing in most scrapbooks and photo albums. This absence emerged for me when I read Catherine Whalen’s description and interpretation of the photo album of Mary von Rosen, “a consummate American girl of the 1920s” (Whalen 79-80). Photographs of her male suitors are a significant subject in von Rosen’s photo album. On the other hand, informal snapshots of fellow Bryn Mawr students are the most common images of people in the collection, attesting to the importance of the friendships which students formed (and still form). Exceptional is the Photo Album of Gladys Stout Bowler ‘09, which contains a number of photographs of men and mixed groups, as in the top scrapbook page to the right, but which consists primarily of off-campus vacation photographs. Much more typical of candids in the scrapbooks and photo albums is the bottom scrapbook page at right, from the Photo Album of Ida W. Pritchett ’14 – these snapshots were all taken on campus, and consist entirely of women. To some extent, this tendency to exclude men from scrapbooks and photo albums simply reflects the reality that Bryn Mawr students would have had few opportunities to socialize with male peers while on campus during this time period. But perhaps it is also an indicator of the Victorian tradition of same-gender romantic friendships at work and of the socially intense homosocial environment which women’s colleges fostered (Faderman, Huebner, Inness, Knotts, Sahli, Smith-Rosenberg, Wilk). Scrapbooks and photo albums offer tantalizing glimpses of relationships, but it can be extremely difficult to know what we’re looking at without information from textual sources about an individual’s social network.

Conclusion

I am only beginning to delve into the content of the scrapbook and photo album collection, and only beginning to come to grips with the challenges of interpreting these priceless objects. This preliminary sketch outlines some notable themes and a few avenues for future investigation. Both collectively and individually, the scrapbook and photograph album collection are rich sources for understanding student life and the identities of Bryn Mawr women – if we can learn how to interpret them.

Bibliography

Brunig, Jennifer L. “Pages of History: A Study of Newcomb Scrapbooks.” Archival and Bibliographic Series of the Newcomb College Center for Research on Women 4 (1993): 1–19.

Deslandes, Paul R. Oxbridge Men: British Masculinity and the Undergraduate Experience, 1850-1920. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2005.

Faderman, Lillian. Surpassing the Love of Men: Romantic Friendship and Love Between Women from the Renaissance to the Present. New York: Morrow, 1981.

Horowitz, Helen Lefkowitz. Alma Mater: Design and Experience in the Women’s Colleges from Their Nineteenth-Century Beginnings to the 1930s. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1984.

Huebner, Karin Louise. The Student Cultures of Athletics and Smashing: Smith College, 1890-1905. MA, University of Southern California: 2004.

Inness, Sherrie A. “Mashes, Smashes, Crushes, and Raves: Woman-to-Woman Relationships in Popular Women’s College Fiction, 1895-1915.” NWSA Journal 6.1 (1994): 48–68.

Knotts, Kristina Lee. The Dissolution of the ‘Emotional Center of Life’: Women’s Friendships in American Fiction (1873-1915). PhD, University of Tennessee at Knoxville: 2010.

Langford, Martha. Suspended Conversations: The Afterlife of Memory in Photographic Albums. Montreal & Kingston; London; Ithaca: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001.

Motz, Marilyn F. “Visual Autobiography: Photograph Albums of Turn-of-the-Century Midwestern Women.” American Quarterly 41.1 (1989): 63–92.

Sahli, Nancy. “Smashing: Women’s Relationships Before the Fall.” Chrysalis 1.8 (1979): 17–27.

Smith-Rosenberg, Carroll. “The Female World of Love and Ritual: Relations Between Women in Nineteenth-Century America.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 1.1 (1975): 1–29.

Whalen, Catherine. “Interpreting Vernacular Photography: Finding ’Me’ – A Case Study.” Using Visual Evidence. Ed. Richard Howells & Robert W. Matson. Maidenhead and New York: Open University Press/McGraw Hill, 2009.

Wilk, Rona M. “‘What’s a Crush?’ A Study of Crushes and Romantic Friendships at Barnard College, 1900-1920.” Magazine of History 18.4 (2004): 20–23.

Pingback: Narrative, Visual Autobiography and Digital Storytelling – New ways to tell Mawter stories | Educating Women

Pingback: Maids, Porters and the Hidden World of Work at Bryn Mawr College: Celebrating Stories for Black History Month | Educating Women

Pingback: Suspended Conversations by Martha Langford | Art & Archives