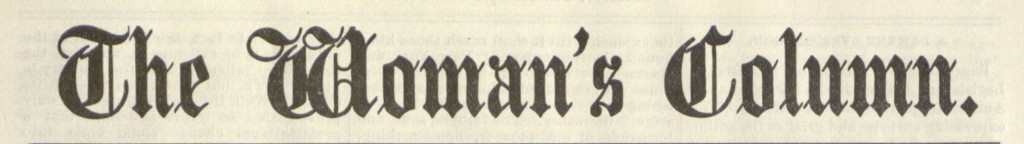

The Albert M. Greenfield Digital Center for the History of Women’s Education is celebrating Women’s History Month with weekly blog posts about The Woman’s Column, a pro-suffrage publication from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This is the third in the series, following our first and second posts.

The Albert M. Greenfield Digital Center for the History of Women’s Education is celebrating Women’s History Month with weekly blog posts about The Woman’s Column, a pro-suffrage publication from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This is the third in the series, following our first and second posts.

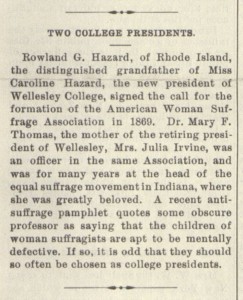

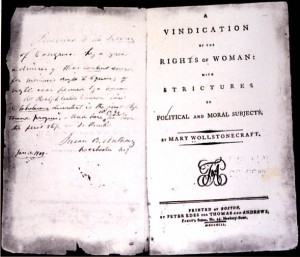

This installment is a direct continuation of our second post, in which we discussed an article entitled “Two College Presidents” from March, 1899. The article sought to prove through the example of two Wellesley College presidents who had been raised by suffrage supporters that the children of suffragists were not “apt to be mentally defective,” as claimed by “some obscure professor” in an anti-suffrage pamphlet. Our post explored the article’s focus on genetic lineage by placing it in the context of the debates that took place throughout the nineteenth century over whether women were physically able to withstand the intellectual strain of education: it was often asserted that women’s reproductive functions would be compromised by such stimulation, a fear that we argue had its roots in an anxious drive to control and limit the acknowledgment (and thus, growth) of women’s societal influence. By placing the emphasis on child-bearing, opponents of advanced education for women were able to keep the conversation tightly focused on the duties of wives and mothers, reenforcing the idea that women’s true responsibilities lay only in that realm. In response, advocates of education suggested that the capacity to perform such duties might in fact be enhanced by education, a perspective seen in Mary Wollstonecraft’s seminal treatise A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: With Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects.

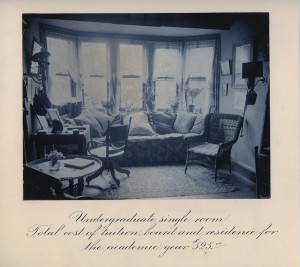

This next post will continue to explore the argument that women ought to be able to pursue education for the advancement of their altruistic duties, rather than at their expense. On March 19, 1892, The Woman’s Column ran a short opinion piece by Ellen B. Dietrick entitled “Educate the Mothers” that was based on the line of thinking mentioned above–that learnéd ladies were better equipped to serve their families–but re-framed it in an interesting and subversive way. In the brief two-paragraph piece, Dietrick encourages women to make financial gifts that support female education in order to maximize women’s potential to exert their influence as “mothers of the race” through civic engagement.

Though she uses the language of the family-focused arguments mentioned above, Dietrick subtly deviates and turns the claim on its head over the course of the short piece. She placates the traditionally-minded reader by situating the “mothers of the race” as the focal point of the article, but she begins and ends her proposal by putting the power in the hands of two different groups: those “who have money to give,” and the “modern college girl” who does not wish to bear children. The first paragraph imitates the tone and view point of past authors who argued for education only so far as it reinforced femininity—yet she opens by placing agency both financially and grammatically, by naming them as the subject of her sentence, in the hands of financially independent women. Her second paragraph re-envisions the concept of motherhood by asserting that childless and unmarried women can still play a nurturing role in society by serving as “intellectual mothers” to underserved populations through community engagement. Rather than empowering women to choose paths other than motherhood, she is proposing that the educated childless woman could actually perform as a super-mother–a “guardian of the poor,” an “intellectual mother to some thousands of children,” a “mother of the race.” Instead of denouncing traditional womanhood, a tactic that would have made her opinion unpopular, she suggests that education could actually amplify the role. The argument is a compromise: she is bound by a framework of accepted norms, but from within that framework she manages to create new ways of viewing women’s agency and potential. Dietrick urges her readers to think beyond literal motherhood and care of a family, and consider the numerous ways in which they could meaningfully contribute to societal good. Ultimately, she argues, the modern college girl need not sacrifice the virtue of the motherly duties she forsakes. Instead, education expands the ways that women can further the good of the race.

Both “Two College Presidents” and “Educate the Mothers” are engaged with the increasingly antiquated view that women are only significant insofar as they wield supportive or corrupting influence over other members of society. The close of the nineteenth century came after several decades of pronounced anxiety about women’s role in lineage, and the extent to which they had the power to shape—for better or for worse—those around them, either genetically or through social practices. One can see the traces of this preoccupation in both pieces: “Two College Presidents” aims to establish that support of equal suffrage would not impair the ability of an individual to parent effectively, and that it does not betray a genetic flaw that could carry forward into future generations. “Educate the Mothers” begins from within the conservative premise that womanhood is only measured in altruistic potential, but manages to turn the focus on the moral woman’s dedication to a cause beyond herself into an argument for increased agency and political voice outside the home.

In her book Learning to Stand and Speak: Women, Education, and Public Life in America’s Republic, our advisory board member Mary Kelley illuminates the connection between the culture of women’s higher education, the growth of female political engagement, and the societal standard for female virtue and morality:

In linking the right to an advanced education to the fulfillment of gendered social and political obligations, post-Revolutionary Americans forged an enduring compromise. Instead of claiming that women had the right to pursue knowledge for individual ends, those who were constituting gendered republicanism debated the boundaries of the domain within which women ought to meet obligations to the larger social good. Those who subscribed to the more conservative model insisted that they deploy their influence only as wives and mothers. Others pressed those boundaries. Although they acknowledged that responsibilities to one’s family remained primary, they asked that women take the lead in instructing their nation in republican virtue.” (277)1

Thus, while women were still not expected to pursue education for the same ends that men could claim–that is, knowledge for the sake of personal enjoyment and development–they were able to carve new avenues of access to education by incorporating it into existing structures of gender. While some perceptions of womanhood were still too deeply-ingrained to buck against with any hope of cultural acceptance, articles like “Educate the Mothers” strove to re-frame the context such that women could continue to move forward and outward one step at a time.

1. Kelley, Mary. Learning to Stand and Speak: Women, Education, and Public Life in America’s Republic. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.