This post is brought to you by Amanda Fernandez (’14) who has been working as a project assistant in Special Collections throughout the summer, specializing in digitizing material for The Albert M. Greenfield Digital Center for the History of Women’s Education. Here she reflects on the difference between digitizing and transcribing oral and written records, both of which illuminate the lives of alums in the past, finding frustrations and fascinations again in comparing epistolary and oral practices in recording memory and interpreting impressions from the past ….

This post is brought to you by Amanda Fernandez (’14) who has been working as a project assistant in Special Collections throughout the summer, specializing in digitizing material for The Albert M. Greenfield Digital Center for the History of Women’s Education. Here she reflects on the difference between digitizing and transcribing oral and written records, both of which illuminate the lives of alums in the past, finding frustrations and fascinations again in comparing epistolary and oral practices in recording memory and interpreting impressions from the past ….

**************************************************************

Summer being almost through, most student workers still happily off at their summer destinations, clinging to what remains of sweet summer and denying the soon to come scholastic year, I have stayed and carried on with my letter transcribing here in Special Collections. In addition to this, in order not to find myself enveloped (no pun intended) in a monotonous workflow, which would eventually incite distaste towards the project (as well as M. Carey Thomas and Mary Garrett), I have taken up another task. The project, which once belonged to Isabella Bartenstein (who is now happily gallivanting about Avignon!), involves listening to and digitizing a collection of interviews of alumna and long retired staff, all in order to compile a digitized collection of the Oral History Project. The project started in 1960 and was an active effort on behalf of the Alumnae Association to collect personal accounts of students’ and staff members’ experiences at Bryn Mawr and how it affected their lives. In 1981, the OHP became more of a collaborative project when the paper work and cassettes were moved to the archives. Caroline Rittenhouse (BMC class of 1952) conducted many of the later interviews and directed the project when she became the College Archivist in 1987. The transferring of these audio tracks from the ancient medium of cassette tape to mp3 on a digital recorder by means of a tangle of wires that turn my workspace into jungle, can be tedious or thrilling, depending on the entertainment and interest value of the interview as a whole. Some of the most interesting interviews turn out to sound more like conversations which is suggested against in the general interview guidelines but, is almost entirely inevitable considering that the dialogue usually occurs between two alums.

I’ve found that audio recorded interviews relay much more information than the hand-written letter does. Letters, more specifically the letters that I have been transcribing, are not capable of lending me as accurate an insight into M. Carey Thomas as would an interview I think. In transcribing and reading the letters, I tend to peel out my own conclusions—imposing my assumptions in order to erect the shadows of two people and a dramatic exchange draped over their correspondence. To be honest, I have gone as far as judging M.C.T. for the way she’s dotted her i’s. In retrospect, something seems obviously askew in that practice—how could I understand enough about the culture of written narrative (which entails so many variables; structure, etiquette and subsequent tone, the relationship between the addressed and the addressee etc.) in that time and setting to mold detailed personalities? I could also draw illusory conclusions from an audio recorded interview if the interviewee is putting on a ‘persona’—but even then, the intuition developed in perception of sound gives the theatrics away.

In listening to interviews I am depending on the human memory—which does not have a reputation for accuracy or precision, especially with the wear and tear of time. Experiences are subjective and the ‘singed’ memories thereafter are much like the newspaper clippings I find attached to letters; they yellow and tear here and there, the paper thins out and sometimes the words that were once clipped for their current relevancy in that time are now relevant in another upon being re-read—sometimes completely transformed by new perception that has been changed much in the same way as the physical clipping. We know that each person will recreate scenarios and memories according to the way they perceive and process—these interviews are unique in that memories are sewn together—memories most times compared and sometimes even confirmed. The exchange of sound waves seems to solidify the person that in letters appears just as a shadow; we are able to build a more three dimensional personality in our heads, we sense their stories in sound, the tone and expression being audible and creating a clearer picture.

Most of the interviews, if not all, are based on a standardized interview format—meaning that each of the interviewers are asking the same questions. Some interviewers ask the interviewee to expand, or they turn the interview into more of a dialogue where one relates to the other, prompting a more enthusiastically responsive and detailed answer. I guess interviews also depend on commonalities and relationship—what the interviewer can draw from the interviewee depends very much on what they have in common in regards to their experience at Bryn Mawr which would allow for the best and most informative dialogue—this also limits the interview in a situation where there is no familiarity. The most intriguing interviews I’ve heard thus far are those that have evolved into conversation due to the binding induced by commonality—such as one between two alums who were both raised by alums. In this exchange they share not only their own experiences (as one time students at BMC as well as what it was like being raised by BMC alums) but also the BMC memories transmitted to them by their mothers. At certain times throughout the recording, I caught the presence of four, each alum and her mother’s memory.

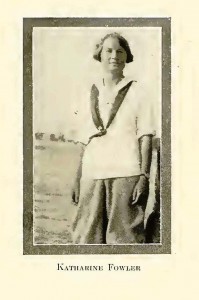

Through these tapes I have also confirmed my own faith in the long standing reputation of exceptional characters that proceeds Mawrters, women that exceed expectation and burst out of the restrictions imposed on them by the social codes of their time. This was clear to me in most of the interviews, but particularly in two, the interview of Katharine Fowler Billings  (class of 1925) who became an accomplished and renowned Geologist in the 1920’s when it was practically unheard of for a woman to take up such a profession.

(class of 1925) who became an accomplished and renowned Geologist in the 1920’s when it was practically unheard of for a woman to take up such a profession.

An article on her pioneering work appears here on the GeoScience World site.

The second was of Isabel Benham who scraped and clawed her way as an independent woman on Wall Street starting in the 1930’s and I could not help but tear up a bit when she remarked, “Bryn Mawr taught you you were the best that there was and you can do anything you want.” Isabel was even dubbed the ‘Mother Superior’ of Wall Street (go to Link to Isabel Benham’s College Yearbook). In both of their interviews, their voices resounded with enthusiasm despite the distance of years from their time at the college and good humor.

Aside from what I have learned from the nature of the medium of audio, I am assured by the content of these interviews that Bryn Mawr women grow to be ‘defy-ers’ of their time.