Last week a comment by G Ragovin on Brenna Levitin’s most recent blog post raised a crucial point, which I believe warrants a response and a call for further thought:

Really really hoping that this winds up being LGB and T, rather than LGb. I’m aware that sometimes discussing trans or gender non-conforming folks adds whole new dimensions to work that genuinely are beyond the expertise or time that a researcher has available, but also that the history of gender non-conforming folks and LGB folks is deeply intertwined, difficult to pull apart because of the ways identity categories have shifted.

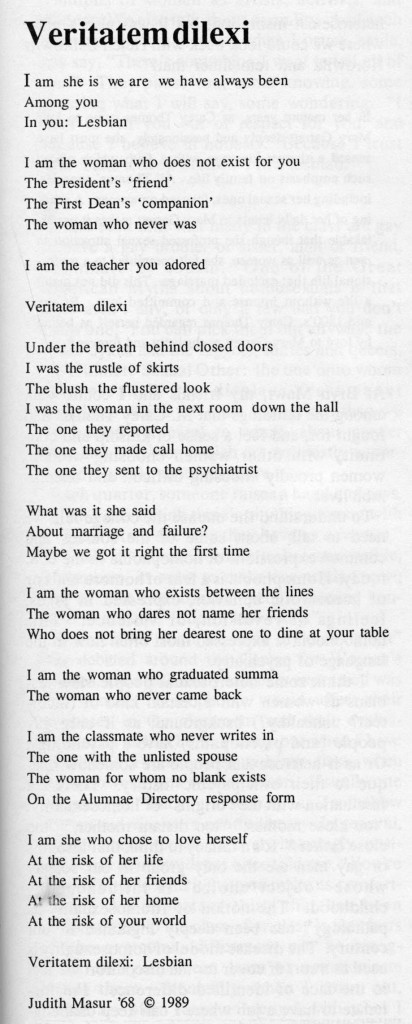

G’s comment reminded me of a couple of aspects of this project that we have not yet addressed on the blog, including how we are grappling with the slippery nature of identity categories over time, and how we plan to represent gender non-conforming subjects in the final product(s). Studying avenues of gender- and sexual deviance in relation to a changing mainstream always poses dilemmas when performing research on historical queer subjects: to excavate stories from the past for a contemporary audience sometimes involves acts of translation that suggest false equivalencies and elide important aspects of historical context. Past  projects have taught me the difficulty of researching queer subjects in the nineteenth century,1 a challenge that G alludes to: “you can ask (and this may not be a useful question for gaining insight into past lives, but you can ask) would some 19th and early 20th c. inverts take to the terminology of the contemporary trans community, if they knew of it?”

projects have taught me the difficulty of researching queer subjects in the nineteenth century,1 a challenge that G alludes to: “you can ask (and this may not be a useful question for gaining insight into past lives, but you can ask) would some 19th and early 20th c. inverts take to the terminology of the contemporary trans community, if they knew of it?”

Any researcher will be confronted with various dimensions of cultural change that make it difficult to draw clean lines between eras when working on queer subjects in the past. These include, among others:

- Evolving vocabularies for describing identity categories

- Shifting politics of identity categories, such as harsher or relaxed stigmas

- Changes in the practices that would mark one as a sexual/gender deviant

- Differences in how people document their sexual and gendered identities in ways that are readable to the future.

As G alludes to in their comment, the inclusive term “LGBT(Q)” tends to be applied very broadly despite the fact that trans* people tend to receive secondary recognition and that their perspectives are often markedly different from cisgender non-heterosexual individuals. In her work on this project for Tri-Co DH, Brenna is striving to incorporate voices beyond Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual, but G was right to suggest that this aspect of the project presents an extra challenge.2 Though less obscure to us than those of the 19th century, even queer histories from the last few decades often resist direct mapping to present-day vocabularies.

In our first oral history interview, we asked our interviewee to comment on recognition of LGBT subjects in the College’s academic course material. He prefaced his response by remarking that “the B[isexual] and T[ransgender] dimensions did not figure, in ’89.” He acknowledged that there were transgender students as well as faculty members on campus at the time, but we have not yet been able to make contact with them in order to establish details or accounts of their perspectives. We have managed to be in touch with multiple transmen who identified as lesbians when they attended Bryn Mawr, and at least one is participating in the project. To what extent do their accounts represent a trans* student experience at Bryn Mawr? Certainly their experiences must be treated as valid and authentic, and yet they will never be able to furnish us with a sense of what it would have been like to navigate the social and academic waters of Bryn Mawr as an out member of a trans* community—nor should they be lumped in with a more generalized lesbian experience, even though they were active participants in lesbian and bisexual communities.

We’re interested in representing a variety of individual experiences without tokenism; a mentality of trying to check all the boxes should not be, and is not, our guiding strategy. Yet it remains a challenge to balance the responsibility of inclusion with an awareness of the complexity of identity and the shortcomings of the vocabularies that we use to describe them. While questions remain about how to frame the contributions of our participants, we will continue to grapple with creating space for authentic T[ransender] voices in this work while leaving room for fluidity both in cultural and personal histories.

Footnotes

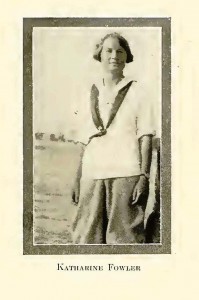

1A classic example of this problem from Bryn Mawr history is the personal life of the school’s second president, M. Carey Thomas. It is well known that she spent most of her life with female companions with whom she was emotionally intimate. However, no source provides perfect clarity on the exact extent of her physical intimacy with either Mamie Gwinn or Mary Garrett, her two long-term partners. Thomas lived in an era in which the convention of the Boston marriage made formalized romantic friendships between women socially acceptable, but such partnerships obviously existed in a different social context from current-day same-sex relationships. Because of her reputation as a staunch feminist and a forward thinker across many fronts, it can be tempting to view Thomas’s associations with Gwinn and Garrett as proto-lesbian relationships. However, to do so is problematic both because it insinuates details of physical intimacy that the historical record cannot confirm or deny, but also because it privileges sexual activity as a marker of legitimacy.

2For excellent recent work on the gender and gender non-conforming individuals at the College, see 2014 Pensby intern Emmett Binkowski’s project History of Gender Identity and Expression at Bryn Mawr College