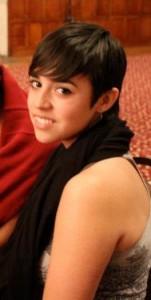

In this post, guest blogger Emily Adams, BMC ’14 reflects on the issue of single-sex education, arguing for the necessity to examine the corporeality of femininity in its fullest sense. Drawing on an essay she wrote for The Albert M. Greenfield Digital Center for the History of Women’s Education Undergraduate Essay Competition this year, Emily explores her thoughts on the often contentious topic of single-sex education today.

Emily Adams is an English major with minors in Russian and Spanish. She has spent the summer interning at a non-profit mental health organization in San Francisco. This fall she will be studying abroad in St. Petersburg.

Feminine Bodies: The Physical Presence of Women’s Colleges

The world is consumed with interest in female bodies. They serve as a constant source of fascination, revulsion, concern and controversy. In pregnancy and childbirth, women’s bodies are worshipped as the origin of life. Through miscarriage, they are condemned as scapegoats for premature death. Nearly ninety percent of those who suffer from eating disorders are women. Teenage girls worldwide are more likely to engage in self-injury than any other demographic. Through Eve, women are even blamed for the genesis of shame and the subsequent covering of the human body. It is clear from these statements that, in much of the world, prospects for women are not overly optimistic. However, at a handful of colleges across the nation, women have been working for over a century to overturn Eve’s sin and reclaim the female form.

It would be absurd to believe that women’s colleges are free from these body-centric obsessions, that the mere existence of a single-sex environment somehow transforms an institution into a secure bubble in which all of the world’s ills can be cured. Single-sex colleges serve, not as a protective sphere to shield students from these issues, but as a stable center from which to confront them. For a young woman leaving high school, undoubtedly self-conscious about her body and her mind, it is an incredible experience to enter a women’s college, a place where every classmate, every friend, and every leader on that campus is another young woman in the process of self-discovery like herself. It is life-changing. The greatest education students of these institutions receive is in coming to accept the female body not only as the center of great suffering, but also unimaginable grace, beauty, and strength.

Studying at a women’s college means being able to lift weights in the gym without competing with male bodybuilders. It means walking into any class, whether it’s computer science or French literature, and knowing you won’t be the only woman. It means being certain that your peers will not take your gender into account when evaluating the merit of your opinions. It means watching the Vagina Monologues and later discussing at the dinner table which monologue rang true for you. Would these conversations take place at co-ed schools? Possibly. Would they invoke the same levels of pride, honesty, and sincerity? Probably not.

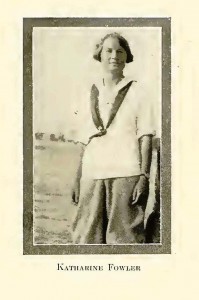

A single-sex education means being surrounded by bright, passionate, involved women— not just in classrooms, but at work, at mealtimes, and in the dorms. It means entering into an enormous sisterhood which extends across all fifty states and most nations of the world, which encompasses several generations of intellectual women and will hopefully grow to include several more in the coming years. It means realizing in the middle of a lecture that, one hundred years ago, a young woman just like you was sitting in that same chair — learning just as you are, rediscovering herself in new and fantastic ways like you — and taking a moment to bask in the glory of our collective history.

For that woman, as well as the millions who have come before and after her in the history of women’s education, every day of her college career was a celebration of her femininity. The simple fact of being at a school filled entirely with women was an affirmation of the power of her gender. She greeted every day with the realization that she was surrounded by people who understood and appreciated what it means to be a woman, what it costs to be female in a male world, and what it takes to change that world for the better. And whether all of those women went on to be rocket scientists or mothers or both, they carried that knowledge with them for the rest of their lives. They knew that, just as their gender should never define them, it should also never be forgotten. They never forgot, and neither will we.

With that in mind, I declare that to live as a woman is the most difficult and most beautiful way to live, and that to spend four years learning with other women is the very best way to understand what that means. I, along with countless others, wouldn’t have it any other way.

For editorial policies on guest blogs please see http://greenfield.blogs.brynmawr.edu/sample-page/