Over the summer, Tri-Co Digital Humanities Initiative intern Brenna Levitin (Class of 2016) began new research into histories of LGBT individuals and communities on campus. What started as a simple question — do materials exist in the Bryn Mawr College Archives to document LGBT life? — led us to new donations from alumnae/i and a rethinking of our digital tools.

We’re pleased to announce that Brenna’s project is now online, accessible through the Greenfield Digital Center’s website:

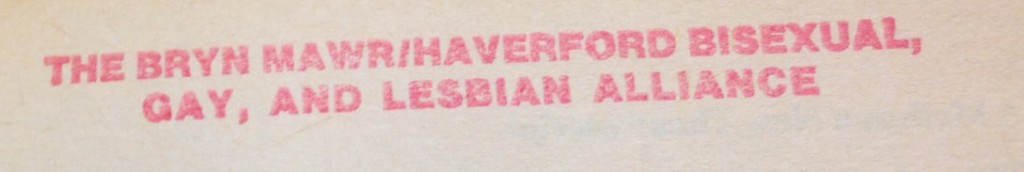

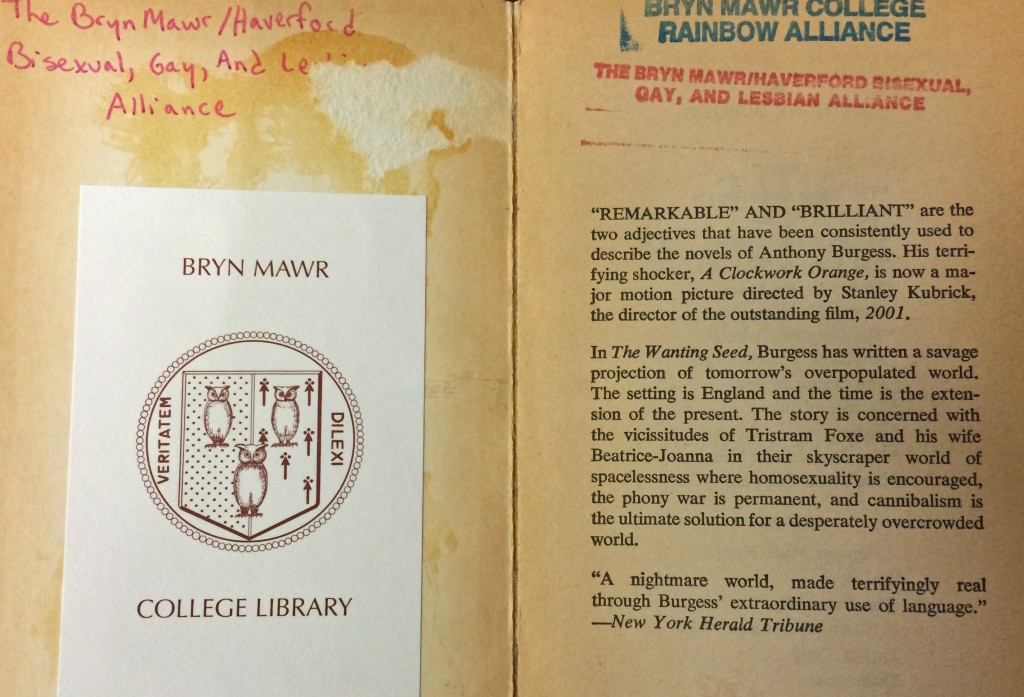

“We Are/We Have Always Been” uses college newspapers, ephemera, photographs, oral histories, and informal interviews to show pieces of a fragmented history that continues to develop in the present day. In doing so, it highlights the multi-linear nature of the narratives that make up personal and institutional memory.

Brenna’s project departs from the form of past exhibits published by the Greenfield Digital Center in that it is built on a platform called Scalar, rather than Omeka. With its flexible approach to narrative, Scalar allowed Brenna to situate parts of the story within and beside one another, in addition to traditional sequential relationships. Brenna’s documentation of this work, including her summer blog posts, lives on as a broader reflection on process; Greenfield Digital Center Assistant Director Evan McGonagill also considered how we might begin to think about the “T” in LGBT histories, particularly in the women’s college context.

We also encourage readers to visit “History of Gender Identity and Expression at Bryn Mawr College,” created by Pensby Center summer intern Emmett Binkowski (Class of 2016) to recognize Mawrters with diverse gender identities. Along with the digital exhibit “A Point of Difference” — recently completed by Alexis De La Rosa (Class of 2015) and Lauren Footman (Class of 2014) to document histories of students and staff of color — these projects reflect the Greenfield Digital Center’s commitment to research that tackles the diverse and challenging histories of Bryn Mawr College and its many communities.

Brenna will return to the Greenfield Digital Center in Spring 2015 through Bryn Mawr’s Praxis program, which will provide an opportunity for her to continue pursuing oral history interviews with alumnae/i and community members.

Comments? Questions? We welcome your thoughts below, or via email to greenfieldhwe@brynmawr.edu.