“Heavy lifting remains to be done in the developing world and women’s colleges are the incubators for the leaders capable of weathering those storms.”

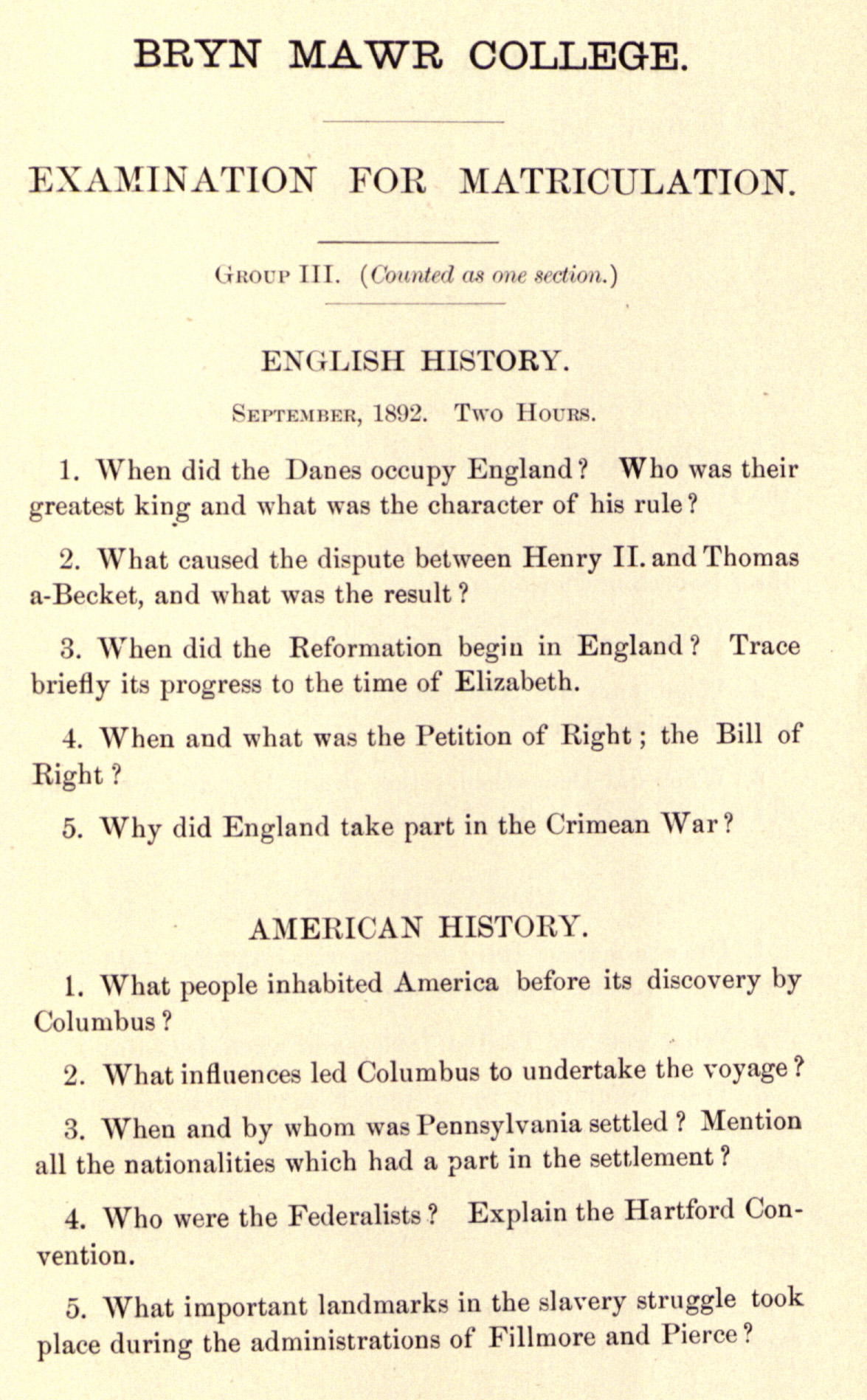

Following our announcement of the student winner of the 2013 essay competition, we are thrilled to name Rebekah Schulz, class of 2006, as our winner in the alumna category! Rebekah wrote a powerful response to the prompt, “Women, education and the future… what do women’s colleges have to offer?” Like many Mawrtyrs, Rebekah did not feel a strong sense of “sisterhood” throughout her college years. It was only later, when she began to apply her Bryn Mawr education to the challenges of post-graduation personal and professional life, that the value and impact of her women’s college experience became clear. Her essay tells the story of how she has learned to apply the “secret reserve of Wonder Woman-like strength and the uncanny ability to solve problems” that she gained from Bryn Mawr in her demanding work in West Africa.

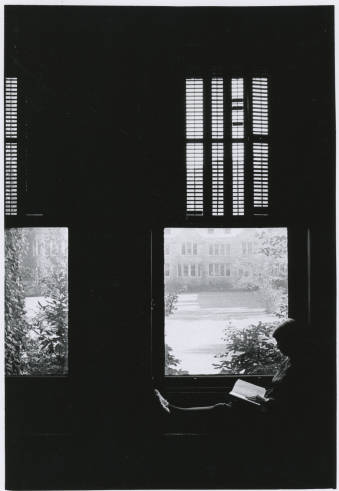

Rebekah gradated from Bryn Mawr in 2006 with a double major in Mathematics and History of Art. She currently works for the US AID Excellence in Higher Education for Liberian Development (EHELD) project. She is based at the College of Agriculture and Sustainable Development at Cuttington University in Suakoko, Liberia, where she teaches geology and soil science and helps to run the library. “Bryn Mawr prepares you to dig in anywhere and anyhow!” She is pictured above at Cuttington Unviersity in October 2013 at a freshman matriculation program with two students that she is sponsoring while they look for scholarships. Rebekah blogs about Liberia and teaching at

lifemagnanimous.wordpress.com.

…

In an increasingly global world women’s colleges are more important than ever before. The goal of higher education is to prepare the next generation of leaders with a moral and intellectual foundation that will keep them grounded during stormy conditions. The women’s movement has made great strides in recent decades and it’s tempting to think women no longer need to be galvanized and steadied for success in a man’s world. Unfortunately that isn’t true in most parts of the world and in the western countries we easily forget that nasty truth. Heavy lifting remains to be done in the developing world and women’s colleges are the incubators for the leaders capable of weathering those storms.

Like most young people I didn’t appreciate college until it was over. At Bryn Mawr I laughed at “sisterhood” and wondered what I’d been thinking. I was sure I could compete with men and I was hungry to prove it! What we all know, however, is that Bryn Mawr teaches you that the only person worth competing against is yourself. You are forced to plant your feet on the ground, focus your eyes, and clear your voice. The opportunity to attend a women’s college is a gift and graduates receive much more than a diploma. They graduate with a decoder ring and a cape (sorry, Double Star, the superhero kind). They graduate with a secret reserve of Wonder Woman-like strength and the uncanny ability to solve problems.

I didn’t realize I had or needed any of that until I moved to West Africa.

In 2011 I joined the Peace Corps and accepted an assignment to teach high school math in Liberia. Boasting Africa’s first female president, Liberia has a lot of girl power. It also has a lot of heartbreaking problems. Girls are less likely to be educated than boys. They are forced into early marriages and start having children at a young age. Women suffered the worst atrocities imaginable during the 14-year civil crisis yet they are ashamed to talk about it. Rape is a family matter.

Walking onto campus as one of two female teachers, the first female math teacher ever, I was intimidated. Then I realized I had the cape and decoder ring. I remembered the only person worth competing against was myself. I didn’t have to compete with the ‘boys’ and I didn’t have to prove anything to anyone. All I had to do was put my feet on the ground, clear my throat, and do the best job I could. When someone said something I didn’t like (such as referring to me as “that little girl”) I had the confidence to politely correct him. When people saw me as a woman and only a woman I had the courage to prove them wrong. When my girl students said, “I can’t” I pointed at myself and said, “Yes, you can!”

I have met remarkable women from all over the world working here. The uniting factor among them is that most attended a women’s college or an all-girls high school. And you can always tell. As soon as she starts talking you can tell she gets it. She sees the world through the same lens you do. She doesn’t let a lack of solutions keep her from trying to solve problems. She has a loud laugh and is unapologetically honest. She’s “almost a man!” as I overheard one such woman described.

In my new job with US AID I teach at an agricultural college, again one of only two female faculty members. It is the definition of a boys club and everyday I say a little prayer of thanks for Bryn Mawr. My four years without men gave me the confidence and strength to compete with them when the stakes are high. It gave me scaffolding and armor for the sexual harassment and ignorance women face everyday in the rest of the world.

When you’re always carrying a weight you forget about it. Attending a women’s college is an opportunity to put that weight down for four years and use that energy for more productive things, like improving yourself. The weight women endure may be reducing in the west, but our sisters in the rest of the world continue to struggle under it, often unknowingly. If we’re serious about changing the world and improving their lives, our lives, we need women’s colleges. The storm may be lifting in America, but it is far from finished.

…