We have been strongly considering the importance of recording experiences of education as part of our work at The Albert M. Greenfield Digital Center for the History of Women’s Education. As part of this, we’ve been digitizing oral histories completed with alums of the past, some who attended the college a century ago. We’ve also recently received some audio interviews of women who featured in the Women of Summer film (about the Summer School for Women Workers, which will also feature as an exhibit on the site soon). So we have been thinking deeply about the ways in which people tell their stories, shape their narratives, and for women especially, how they fit the story of their education into the wider narrative of their lives.

How do people memorialize important experiences such as higher education? Have there been changes over time? What is remembered and what is forgotten? What new forms of scrap-booking, such a popular past-time in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century (with a recent revival in the context of renewed interest in crafts) now exist or can exist in the digital world?

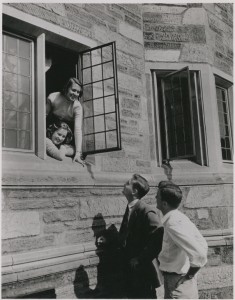

Excerpt from Photo Album of Eva Levin Milbouer, Class of 1933. See this at http://triptych.brynmawr.edu/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/BMC_scrpbks&CISOPTR=6030&REC=6

As Jessy Brody’s posts in this blog on her work on the Bryn Mawr collection of scrapbooks indicates, they are rich source of material for researching past lives at Bryn Mawr College. They do not, as she has found, always tell you what you would wish to find out, being as they are, silent testimonies to the lives of Mawters in the past, communicating visually but not aurally or orally the myriad of academic and leisure experiences they had during their time here. Jessica Helfand, author of Scrapbooks: An American History has argued that scrapbooks are a form of visual autobiography to record and commemorate things that could not, for whatever reason, be expressed in words:

‘The scrapbook was the original open -source technology, a unique form of self-expression that celebrated visual sampling, culture mixing, and the appropriation and redistribution of existing media” (page xvii)

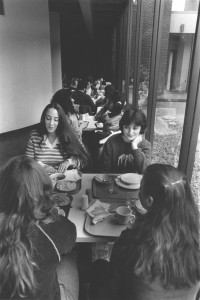

We are hoping to extend our knowledge about past experiences at Bryn Mawr College by collaborating with alums in creating digital stories, a new form of visual autobiography which melds aspects of scrapbooks with oral history to create unique personal stories.  Traditional elements of scrapbooks – photographs, letters, notes, invitations, ephemera and other reminders of past experiences – are scanned and combined with an audio narrative to create an audio-visual file that looks somewhat like a mini-movie. Having been inspired by the pedagogical work in bringing digital storytelling into the classroom at the University of Richmond we have adjusted their principles of creating digital stories to reflect the needs, interests and experiences of Bryn Mawr alums (for some great examples of digital story telling from the Richmond site click here).

Traditional elements of scrapbooks – photographs, letters, notes, invitations, ephemera and other reminders of past experiences – are scanned and combined with an audio narrative to create an audio-visual file that looks somewhat like a mini-movie. Having been inspired by the pedagogical work in bringing digital storytelling into the classroom at the University of Richmond we have adjusted their principles of creating digital stories to reflect the needs, interests and experiences of Bryn Mawr alums (for some great examples of digital story telling from the Richmond site click here).

I will be working with alums through city and regional Alumnae Club chapters to assist interested Mawters in creating their own reflective pieces on their time at Bryn Mawr. The story you wish to tell is completely up to you: perhaps you would like to represent why you chose Bryn Mawr College above others? Or your experiences at a single-sex institution? Or what you think being educated at Bryn Mawr gave to you throughout your life/career? Was it a special time, a challenging time, or a mix of both? What role does a single sex educational institution have to play in the landscape of higher education today? These are merely suggestions; the digital story is truly yours. For more information on our approach to creating digital stories, click below to see a poster on the topic.

I will be working with alums through city and regional Alumnae Club chapters to assist interested Mawters in creating their own reflective pieces on their time at Bryn Mawr. The story you wish to tell is completely up to you: perhaps you would like to represent why you chose Bryn Mawr College above others? Or your experiences at a single-sex institution? Or what you think being educated at Bryn Mawr gave to you throughout your life/career? Was it a special time, a challenging time, or a mix of both? What role does a single sex educational institution have to play in the landscape of higher education today? These are merely suggestions; the digital story is truly yours. For more information on our approach to creating digital stories, click below to see a poster on the topic.

Bryn Mawr Digital Stories for The Albert M. Greenfield Digital Center for the History of Women’s Education

If you are interested in creating your own digital story, think about doing so as part of your local alumnae chapter and feel free to contact me any time (jredmond@brynmawr.edu)

Collecting Bryn Mawr stories is a supplement to our other work of digitizing the oral history interviews conducted in past decades which are currently on cassette tape (for more on this see blog post by student worker Isabella Barnstein on her work on creating a catalog and digitizing the collection).

Capturing the varied narratives and preserving them for future generations is an important aspect of our work and one that we hope will interest alums and the wider community of those who research, teach and simply like to hear about women’s past experiences in education.

Capturing the varied narratives and preserving them for future generations is an important aspect of our work and one that we hope will interest alums and the wider community of those who research, teach and simply like to hear about women’s past experiences in education.

As a reminder, you can view the scrapbooks we have currently digitized in Triptych by clicking this link (there are currently 22 albums in the collection with ongoing digitization as part of the Greenfield Digital Center initiatives in digitizing important Bryn Mawr College material).

Happy browsing!