It’s fall break at Bryn Mawr, and I’ve been traveling to share work with colleagues at the Oral History Association’s annual meeting in Madison, Wisconsin. As someone who has been teaching, advising, and doing oral history research for just over two years, this was my first visit to the OHA, and it was an energizing meeting of scholars and other practitioners from around the country. The conference was an opportunity to think critically about the stories we collect and who tells them; given our work at the Greenfield Digital Center, I was excited to spend a lot of the conference talking about (and listening to) histories of higher education, and women’s higher education in particular.

I had been invited to present at the OHA by American Studies scholar Carol Quirke, who is documenting the founding years of her institution — SUNY College at Old Westbury — with the site Experiments. Together with CUNY oral historian Sharon Utakis, our panel, “Places of Privilege, Places of Struggle: Oral Histories of Activism and Movement Building in the University” considered how oral history projects with the stated purpose of collecting evidence of social movements on campus “live” in University collections, and how they might inform current campus conversations. My paper, drawn from projects I previously directed at the University of Chicago, focused specifically on pedagogy, and what it means for oral history interviews to be the meeting point between past and present LGBTQ student activists. As the project Closeted/Out in the Quadrangles: A LGBTQ History of the University of Chicago enters its fourth year of work, and as I’ve moved on to Bryn Mawr, I find myself more and more compelled by the idea of college campuses as intergenerational sites of history and memory, with possibilities for current students, alumnae/i, faculty, and library staff to work together in expanding the scope of what counts as campus history.

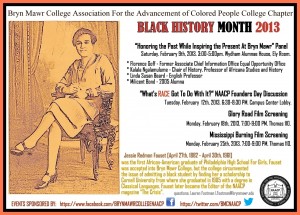

I couldn’t help using the conference as a place to share the oral histories Brenna Levitin, Class of 2016, collected this summer as part of her digital project “We Are/We Have Always Been”: A Multi-Linear History of LGBT Experiences at Bryn Mawr College, 1970-2000. Brenna’s research will continue on next year, as will other projects chronicling less-known stories in Bryn Mawr’s past. As I noted in my conference paper, I have reason to be hopeful for continued engagement with these new histories. Our work is indebted to the worlds of feminist and queer archiving as they have expanded and spread into institutions like the university and independent collections over the past few decades. “For a younger generation of feminists,” Kate Eichhorn writes in The Archival Turn in Feminism, “the archive is not necessarily either a destination or an impenetrable barrier to be breached, but rather a site and practice integral to knowledge making, cultural production, and activism.” Her premise can be illustrated, on a small scale, at the university and college archives where I’ve worked: our classes and programs can draw new audiences — students involved with campus organizations — who feel that we might offer a productive space in which to explore an activist and social history.

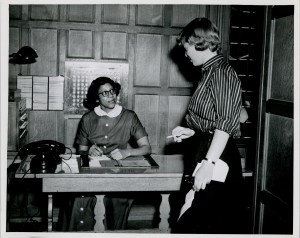

In between giving my paper Thursday and presenting at Saturday’s oral history community showcase, I was excited to grab a seat at Friday’s standing-room only panel, “Current Feminist Practices of Oral History,” featuring a comment by Sherna Berger Gluck — whose 1991 edited collection Women’s Words: The Feminist Practice of Oral History is still used in women’s history classrooms. If, as Gluck contended, feminist oral history originated as a radical experiment, how are we still experimenting in our research and teaching? Kelly Sartorius, from Washington University in St. Louis, gave an important example of how oral history interviews can drive a research agenda. In her presentation “From a Life History into the Archives,” she argued for a “feminist life history approach.” Sartorius charted how she used the worldview of one narrator, University of Kansas Dean of Women Emily Taylor, to guide her work in the archives, and move away from the “waves” metaphor usually used as shorthand for mainstream feminist activism in the U.S. context. If we often talk about student protesters as the leaders in “second wave” feminist agitation on campuses, Sartorius’s research recovers the work of feminist university administrators, working with and for student activists in the middle decades of the twentieth century. Her new book, Deans of Women and the Feminist Movement: Emily Taylor’s Activism (Palgrave, December 2014) will certainly be on my winter break reading list.

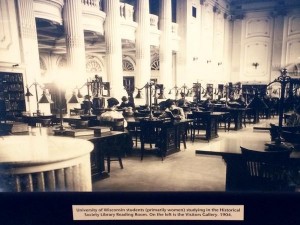

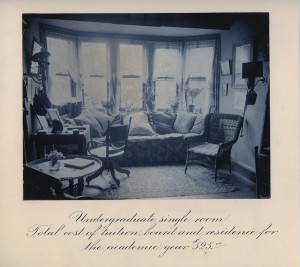

Before leaving town, I also had a chance to stop in to the Wisconsin Historical Society, where I followed up on my research into Catholic women’s education at the turn of the century. I found exactly what I was looking for in the library’s historical pamphlets collection, with the added bonus of finding traces of women’s education history throughout the Society’s halls. Like other midwestern “land grant” universities, the University of Wisconsin admitted women “to the full advantages of the University” in the 1860s. (Having just filed my course proposal for next semester, when I’ll be teaching histories of women’s higher education in 19th and 20th century America, I was excited to see a turn-of-the-century photo of women students at work prominently displayed next to the reference librarian’s workstations!)

Although my Madison sojourn has come to a close, readers can still view our conference discussions on Twitter with the hashtag #OHA2014. The call for proposals for next year’s meeting, “Stories of Social Change and Social Justice,” was announced in the conference’s printed program; in the meantime, the Oral History Review will be recapping other important conference conversations. Given our ongoing project to digitize Bryn Mawr oral history interviews (currently languishing on cassette tape) and support new interviews conducted by our students, there’s much more to come.