Following on from our previous posts by Bryn Mawr College student worker Amanda Fernandez (click here to see her first post specifically on the Thomas collection letters), I’m returning to the topic of letters from a different perspective – what the letters between M. Carey Thomas and Mary Garrett reveal about their relationship, and Garrett’s important role on campus during her life here with Thomas.

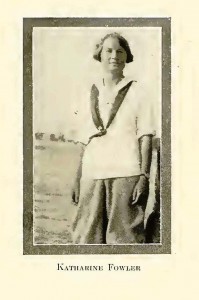

Mary Garrett

M. Carey Thomas

Before addressing the letters in details, I wanted to include a quick update about how the letters will appear on our site…

Letter from Mary Garrett to M. Carey Thomas, 1880. The letter details Mary's recent failure in an examination, which left her feeling embarrassed and deflated. She looked to Thomas as an inspiration in academic terms for her success in passing university exams and going to Europe for her doctoral studies

The letters will be featured in two ways on the site: as a collection which is searchable, showing both digital scans of the original letters (such as you see on the left) and their transcriptions, and as an online Omeka exhibit, which I will be working on in the coming months. The former method will allow for the searching of the letters by year and tag, for example, geographical place, and detailed summaries will be provided on the content.

These are currently being transcribed and the earlier years of their correspondence will appear first, with the collection growing as transcripts are produced. The exhibit, like the others on the site, will lead you through the broader narratives of their letters and the events of their lives, first as friends within a social circle that included shared friends and activists, later as living companions and fellow suffragists.

As Kathleen Waters Sander, Mary Garrett’s biographer has noted, Garrett was a figure of much interest in her day, but sadly her name has been somewhat forgotten in the realm of philanthropy and activism. As Waters Sander comments in Mary Elizabeth Garrett: Society and Philanthropy in the Gilded Age (Johns Hopkins University Press: 2008), Mary was

a favorite of the turn-of-the-century press, who were fascinated by her unique combination of wealth, activism, business expertise, and extraordinary philanthropy. She became one of the country’s most publicized women, unselfishly using her money and status to transform women’s lives and to break down the barriers that prevented women’s equal participation in society (page1)

Born into the wealthy Garrett railroad family of Baltimore, Garrett grew up with a sense of purpose about her wealth; she wished to use it for altruistic means, to benefit society. She also wished to use her wealth to enhance women’s access to higher education and to professional medical education, providing educational opportunities to them that, ironically, she herself was not able to partake of. In the letter shown above, Garrett wrote to Thomas after her failure to pass the Harvard Examinations for Women (an exam regarded as a benchmark for accrediting women’s learning but this did not allow them access to Harvard University) which her friend Julia Rogers had just passed. Garrett felt herself to be unable to reach the high levels of academic achievement Thomas had attained in completing her degree at Cornell University, and Thomas was at that time preparing to take up her doctoral work in Liepzig, Germany. In this excerpt from a letter from June 10th 1879, Garrett’s tone of congratulation is tinged with sadness that she is losing a friend who has been an encouragement to her:

._ Your letter ought to act like a tonic_ It is so good to hear of the people who really are at work, even if one can not be of them I think I can say, Minnie, that I am truly glad you are going, but it will be a tremendous loss for us _ I wonder whether you know how much I have grown to care for you in the last two years + what a help + encouragement you have been for me_*

Again, as I have written elsewhere in this blog, Garrett felt that her difficulties in academic achievement could be linked to medical problems with her uterus:

… Dr. Jacob will not nearly be encouraging as I had hoped. Of course she says I can study even this summer a couple of hrs. a day, if I like; but that I shall probably never be able to work eight or nine hours a day + altogether I am freed to the conclusion that I was not cut out for a student either mentally or physically _ I am going to see her on Friday or Sat. for all examinations about that trouble wh. you may remember she said i had behind the uterus + wh. I am afraid is not very much better + as you can imagine, I am not looking forward to the visit with much pleasure.*

Garrett did confess to procrastination in her study in this letter, but her prose clearly indicates a belief that she did not have the physical capacity to study due to problems with her gynecological organs. Waters Sander has attributed Garrett’s stifling, conservative world in which her father prohibited her from pursuing marriage, college or a career, as the cause of her mental collapse, or ‘neurasthenia’ in Victorian terms, at the age of 25.

Despite her own health challenges and her lack of confidence in her own intellectual abilities, Garrett displayed true altruism, particularly her important role in the history of Bryn Mawr College, which, while documented, is not remembered to its fullest extent. Much like Garrett’s positive attitude to women’s education in general despite her own prohibition from academia, she generously supported (both financially and emotionally) M. Carey Thomas’ bid to extend her cultural education through trips abroad and to obtain the position of President at Bryn Mawr College Thomas so desperately craved (for more on the details of this support, see the excellent Thomas biography by Advisory Board member Helen Horowitz, The Power and the Passion of M. Carey Thomas). Garrett’s family had a strong sense of purpose in their civic activism in Baltimore, and this undoubtedly influenced her decision to open the Bryn Mawr School for girls in 1885 in Baltimore (along with Bessie King, Mamie Gwinn, Julia Rogers and Thomas, the Friday Night group) to educate girls for the entry requirements to any colleges that would allow them to enter. This school would open horizons for girls that these women had not had the opportunity to gaze at and the college preparation mantra of the new establishment ‘flew in the face of all conventional wisdom at the time’ on appropriate education for women as Waters Sander has observed (Mary Elizabeth Garrett, page 125).

Thomas was an active writer and her letters to Mary reveal her personal concerns and emotions which she often sought to keep private and distinct from her professional persona as Dean and then President of Bryn Mawr College. Even before assuming these roles, Thomas shared her challenges studying for her doctorate in Europe to Garrett, detailing her struggles not just with the work but also with the attitude towards women as they were studying. Carey’s letters to Mary in late 1879 revealed the harrassment she received from some of her male peers at the University of Leipzig, which she felt was their way of trying to chase out the women, an experience she warned Garrett and their friends to keep secret lest her family find out and demand her return to America. As is well known, Thomas eventually triumphed, receiving her doctorate summa cum laude from Zurich and returning to the US to embark on her strategy to be a serious scholar and to take control of Bryn Mawr College.

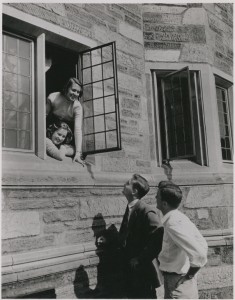

Thomas and Garrett lived for many years together at the Deanery which Garrett lavishly decorated with works of original art and fine furniture. The Deanery was, as well as a private residence for Thomas and Garrett (and Mamie Gwinn before her), a formal entertainment space used for faculty parties, dinners for visiting speakers and for student teas and other entertainments (which as you can see in this excerpt from the scrapbook of Lorraine Mead Schwable (class of 1912), included both Garrett and Thomas’ names on the printed invite).

As you can see in this picture of Mary Garrett enjoying May Day celebrations on campus,

As you can see in this picture of Mary Garrett enjoying May Day celebrations on campus,  she was a well known figure and a feature of life at Bryn Mawr College and participated fully in its social calendar. Scrapbooks also reveal, as Jessy Brody has documented in her blog post on candids and ephemera, that invitations from Thomas and Garrett’s were items kept by students in documenting their important moments at the college. As the invite particularly underscores, as well as the photographs of Garrett at May Day, she was quite clearly regarded as Thomas’ respected friend and companion and had a role of importance at the college. We must conclude, therefore, that whatever opinions people have/had on the nature of their relationship, it was recognized and accepted that Mary Garrett had an important role in Thomas’ life and that she enjoyed an elevated status at the college because of this and her Deanery connections.

she was a well known figure and a feature of life at Bryn Mawr College and participated fully in its social calendar. Scrapbooks also reveal, as Jessy Brody has documented in her blog post on candids and ephemera, that invitations from Thomas and Garrett’s were items kept by students in documenting their important moments at the college. As the invite particularly underscores, as well as the photographs of Garrett at May Day, she was quite clearly regarded as Thomas’ respected friend and companion and had a role of importance at the college. We must conclude, therefore, that whatever opinions people have/had on the nature of their relationship, it was recognized and accepted that Mary Garrett had an important role in Thomas’ life and that she enjoyed an elevated status at the college because of this and her Deanery connections.

Thomas and Garrett shared much in their ambitions for women in their contemporary society and worked closely on issues such as suffrage and access to higher education. Helen Horowitz has argued that it was Garrett who facilitated Thomas in being more public and vocal in her advocacy of women’s rights, particularly in expanding her realm of interest from access to higher education into suffrage and women’s role in the public sphere. Their letters reveal their shared aims, their intellectual exchanges, joint passions for art, literature, poetry and engagement with prominent scholars of their time, and their very different personalities that somehow seemed to work together in creating partnership, friendship and intimacy that lasted over four decades.

More will be explored in the forthcoming Omeka exhibit about their letters and what they can reveal to the historian about the influence they had on each other throughout their lives. In the meantime, keep reading the blog for further updates!

* With thanks to Amanda Fernandez for creating the transcription of Mary Garrett’s letter.

Lesbian Herstory Archives Internships

Lesbian Herstory Archives Internships