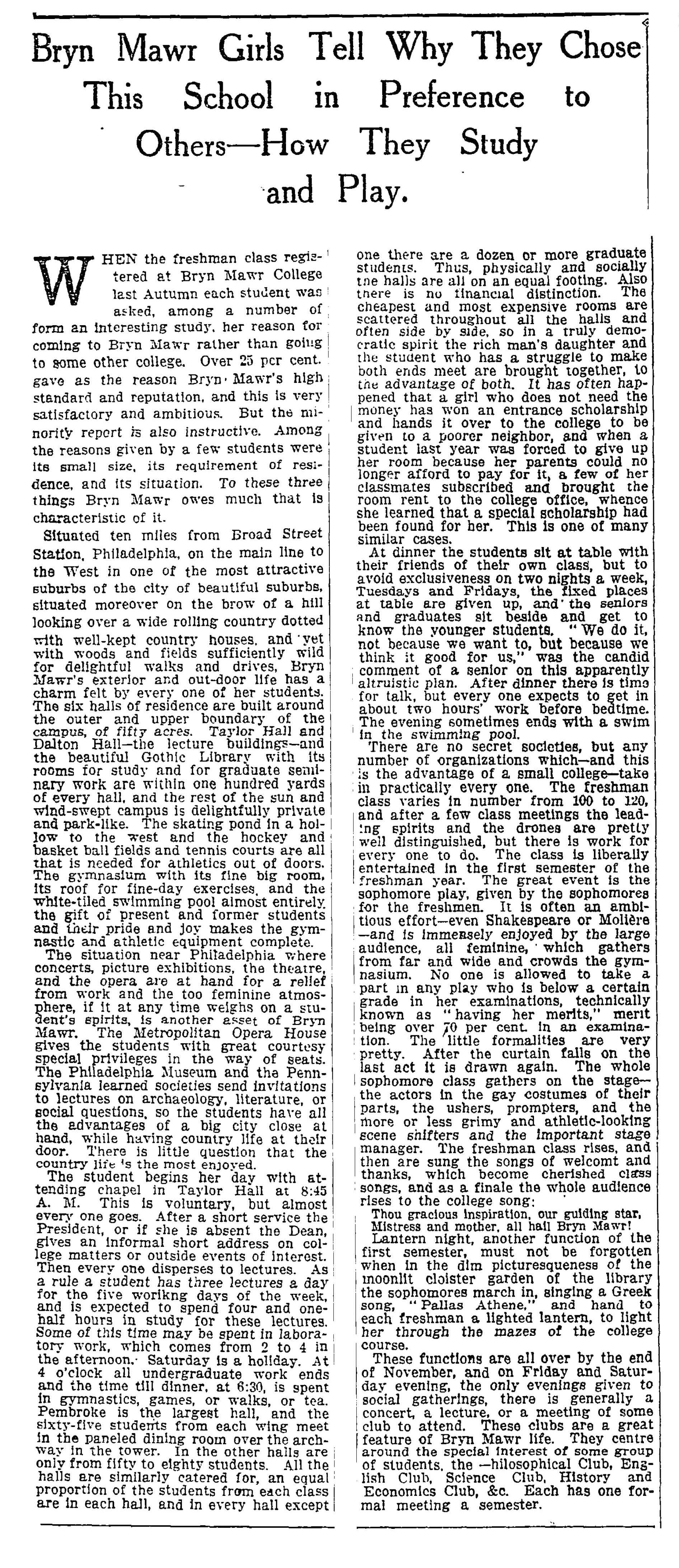

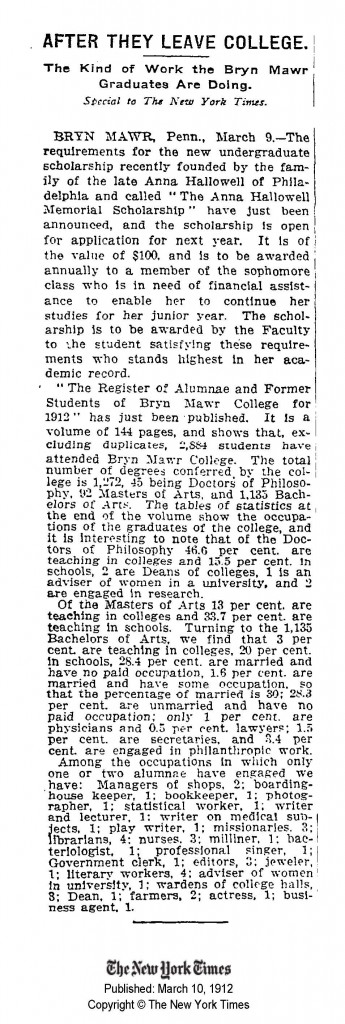

Since May, Brenna Levitin, the Greenfield Digital Center’s TriCo DH summer intern, has been hard at work tracking down the histories of LGBT individuals and communities at Bryn Mawr between 1970-2000. To catch up with her work, read Brenna’s thoughts on one of her first finds, her consideration of silence in the archives, and her approaches to using digital tools to address the silence, including reflections on making the Digital Center’s first Scalar project. We look forward to launching Brenna’s project, We Are/We Have Always Been, next week–stay tuned!

Brenna Levitin, Class of 2016

Let’s hear it for victories! Although much of the past four months has been spent sighing over a lack of LGBT archival material, I recently had a great realization which partially solved the mystery of the disappearance of Bryn Mawr’s BGALA Center Library. I first heard about this mystery from Robin Bernstein, Class of 1991, the creator of the library and its first keeper. She told me about how she painstakingly shaped it over three years, only to have it disappear a few years after she graduated. She mourned the multi-hundred-volume library for years, until, to our excitement, I physically ran into the collection in Canaday Library a few weeks ago! Here’s a short retelling of the library’s saga.

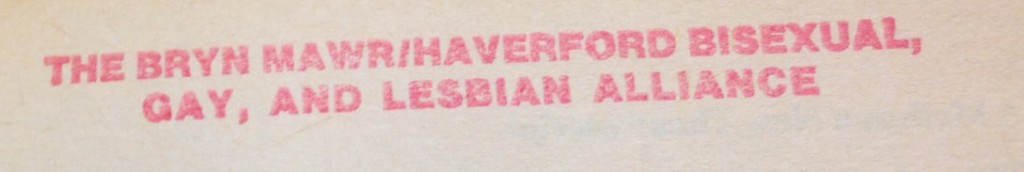

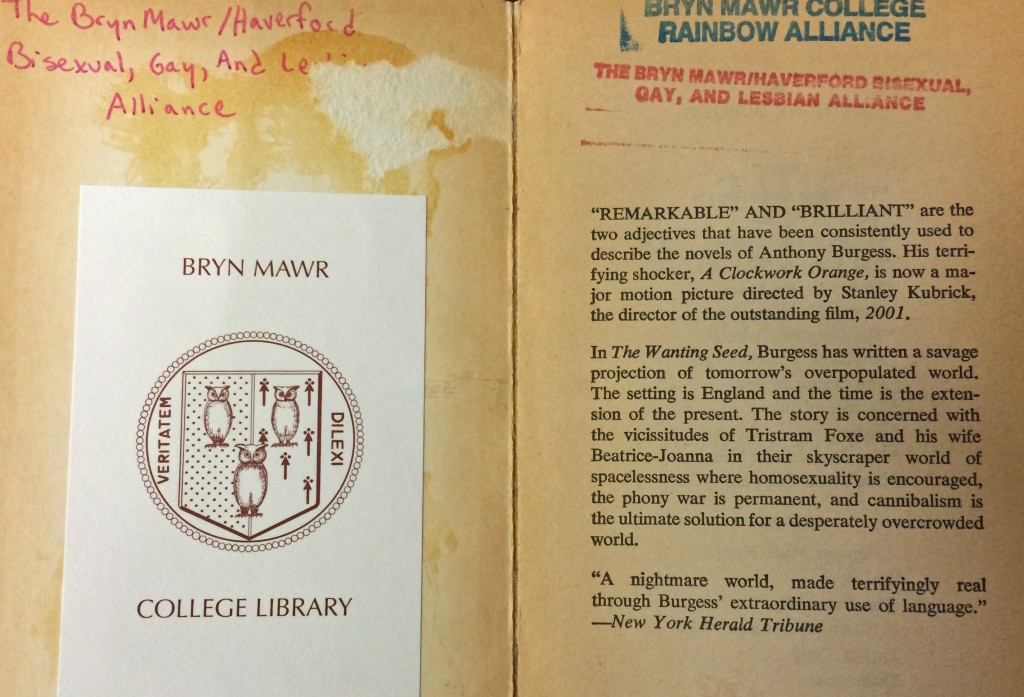

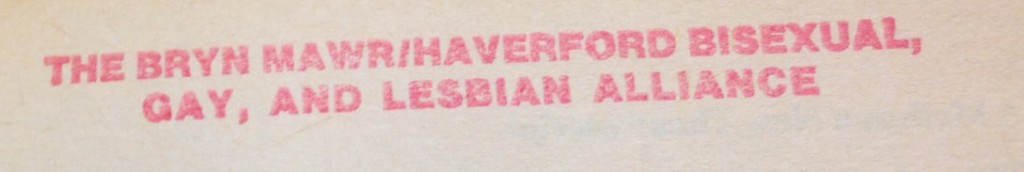

In her sophomore year, Robin Bernstein asked the Bryn Mawr Women’s Center to use their empty back room as a physical space for BGALA (The Bryn Mawr-Haverford Bisexual, Gay, and Lesbian Alliance). After the students in charge agreed, Bernstein began to create a physical space for the club within the Women’s Center, located on the upper floor of the Campus Center. To fund decoration and set-up of the space, Bernstein wrote a grant and received $1,000, in addition to the money BGALA received from general SGA budgeting. She took approximately $1,500 to the Owl Bookshop on campus and to Giovanni’s Room–the famous bookstore in the Philly Gayborhood–and bought as many books as possible. After carting everything back to campus, BGALA members rubber-stamped everything “The Bryn Mawr/Haverford Bisexual, Gay, and Lesbian Alliance.”

BGALA Library stamp, as seen in Lesbian Plays (New York: Methuen, 1987-1989), Canaday Library Rainbow Alliance & Women’s Center Collection, PR 1259.L47 L4 1987 v.2.

Bernstein lovingly curated the library for the next three years, watching as it grew with each year’s funds. By the end of her senior year, the library contained over 1,000 books, audiotapes, and magazines. The summer after Bernstein’s graduation in 1991, the books were removed from the BGALA Center and relocated to a room in the Denbigh dormitory. Previously, the BGALA library was unstaffed, functioned on the honor system, and was heavily used. After their move, no one knew where to find the books, and so they saw less use as the years went on.

After approximately 1993, institutional memory fails to recall where the books lived. In fact, Bernstein and I believed the books to still be missing when I found them, by chance, living in Canaday Library as an official collection. By working backwards and talking to library staff, I was able to piece together part of their journey post-Denbigh.

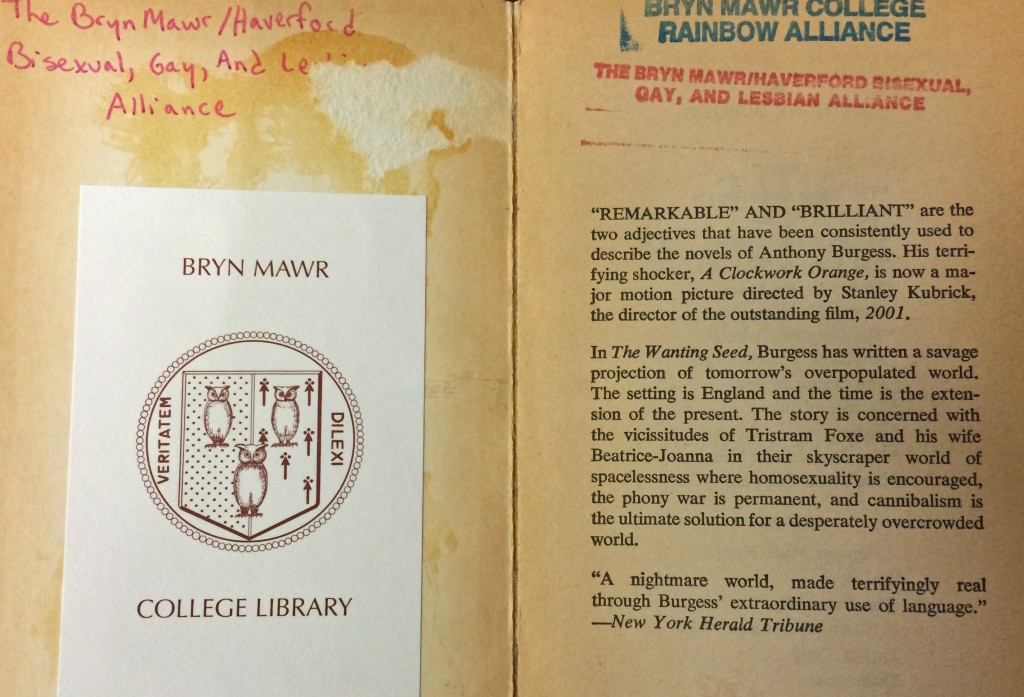

Layers of library history, as seen in Anthony Burgess, The Wanting Seed (New York: Ballantine Books, 1964), Canaday Library Rainbow Alliance & Women’s Center Collection, PR 6052.U638.

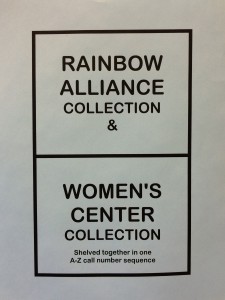

The next time that anyone saw the BGALA books was in 2003, when members of the Rainbow Alliance came to then-Coordinator for Information Acquisition and Delivery, Berry Chamness, in Canaday to ask for help. The Rainbow Alliance (the new name for BGALA) was losing the space where they stored the library, and wondered what to do to save the books and keep them accessible. Since Fall 2004, what is now known as the Rainbow Alliance/Women’s Center Collection has lived as a discreet collection in Canaday Library, and can be found on the shelf closest to Quita’s Corner by the back window on the first floor.

The Rainbow Alliance & Women’s Center Collection is now catalogued in TriPod and shelved on the first floor of Canaday.

I’ve put together the history above from personal accounts and some library sleuthing, but there are still pieces missing from the puzzle. What happened to the books between 1992 and 2003? Were BiCo students aware of the books as a resource, and who was responsible for them? If you have a piece to add to the puzzle, please email greenfieldhwe@brynmawr.edu or comment below! I’d also love to hear from anyone who remembers the library in any of its incarnations.

Interested in the Rainbow Alliance/Women’s Center Collection holdings? We’ll be sharing our favorite books on the Greenfield Digital Center tumblr this fall!