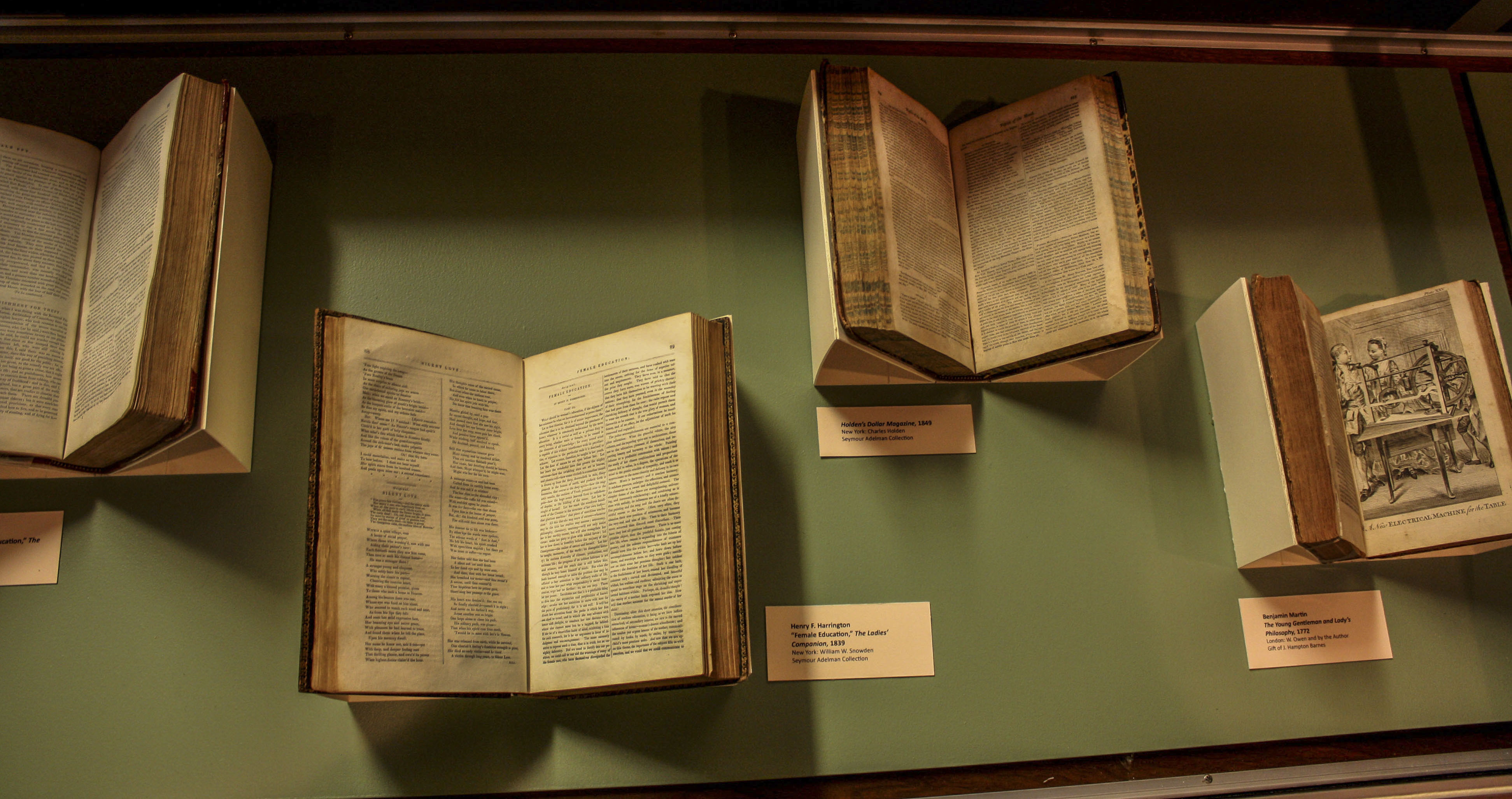

Marion Park, President of Bryn Mawr directly after M. Carey Thomas. Park was a Bryn Mawr College alum and is the subject of a new exhibit to be developed over the summer for the website

The summer is here and we thought we’d share our plans for developing the Center’s site with you. We will be working hard over the next few months on developing new content, and continuing to reach out to you on social media (if you don’t follow us already, get to it @GreenfieldHWE or find our facebook updates on the Friends of Bryn Mawr College Library page).

We are excited to be making two significant improvements to the site. The first of these is to make the site mobile compatible, so all of you who like to browse on your tablet or phone will be able to do so more easily once the changes come into effect around July. The second improvement is something that more directly affects our experience – we are in the process of upgrading to the new Omeka 2.0 platform, a huge improvement on the previous version from our initial poking around! If you are using the new platform and would like to share your experiences, be sure to get in touch (greenfieldhwe@brynmawr.edu). The biggest change on the user end will be the search functionality, which will be greatly enhanced from its present version. Aside from the search, users will not notice differences or disruptions (we hope!) but the streamlined back end is definitely an improvement and will help us in our mission to digitize and display in the best way the resources we hold in the history of women’s education.

Marian Edwards Park was President of Bryn Mawr from 1922 until 1942 when she retired. When she came to Bryn Mawr as a student she was among the early generations of women who enjoyed higher education for the first time. A member of the class of 1898, she won the European Fellowship upon graduation, the college’s highest honor at the time. She returned to complete her PhD in classics in 1918. She therefore experienced life at Bryn Mawr from all perspectives: undergraduate, graduate and administrator. She oversaw the school through some dramatic times, namely the Depression and the beginning of World War II, and she was also president during the period in which it first allowed African American students to attend as undergraduates and as members of the Bryn Mawr Summer School for Women Workers. Park also led the celebration of the College’s 50th anniversary, a major milestone of achievement in the ‘experiment’ of education for women. Because she followed in the rather intimidating shadow of M. Carey Thomas, her contributions have not loomed as large in the historical record. However, Park will be the subject of a new exhibition this summer, examining in particular her condemnation of the increasingly horrifying events in Europe that led up to World War II. The exhibit will include evidence on her efforts to host Jewish scholars fleeing the Nazi regime. Keep an eye on the site for the exhibit and make sure to let us know what you think.

We hope to continue work on digitizing primary sources, particularly the rich collection of oral histories that we have been engaged in translating from cassette tapes to digitized recordings for over a year. This is slow, meticulous work, but we hope to be able to share them with you eventually on the Tri-College digital collections site, Triptych. If you haven’t seen them already, there are a few examples from the collection that were digitized as part of the Taking Her Place exhibition, available on our site here. This is a fascinating collection, including narratives from student, staff, faculty and alumnae, with memories stretching back to the first decades of the college’s existence. Work will be ongoing for the next year and more, but we will be releasing recordings to celebrate special events or for use in digital exhibits as appropriate when we can do so. There have been a few reflections from students working on this collection over the past while which you may have seen already, the last of which was by our most recent student helper on the project, Lianna Reed ’14.

Special Collections is also hosting a number of interns for the summer, two of which have been awarded brand new internships through the Pensby Center to focus on tracing histories of diversity at Bryn Mawr College. Lauren Footman ’14 will be examining the experiences of the African diaspora on campus, including sourcing participants to create new oral histories to add to our collection, a most welcome addition to our work at the Center in trying to uncover stories from that past for which we have little or no documentary evidence. Her fellow intern, Alexis de la Rosa ’15, is looking at Latina histories and will be surveying current students and alums later in the summer. Alexis and Lauren’s work will be available as a digital exhibit on our site at the end of the summer, and they will also be writing blogs about their experiences doing this important research. Both Alexis and Lauren are also jointly engaged in cataloging the papers of Evelyn Rich, class of 1952. Evelyn Rich was one of the first African American students to live on campus, and her extraordinary achievements span education, the labor movement and politics. We are lucky to have acquired her papers.

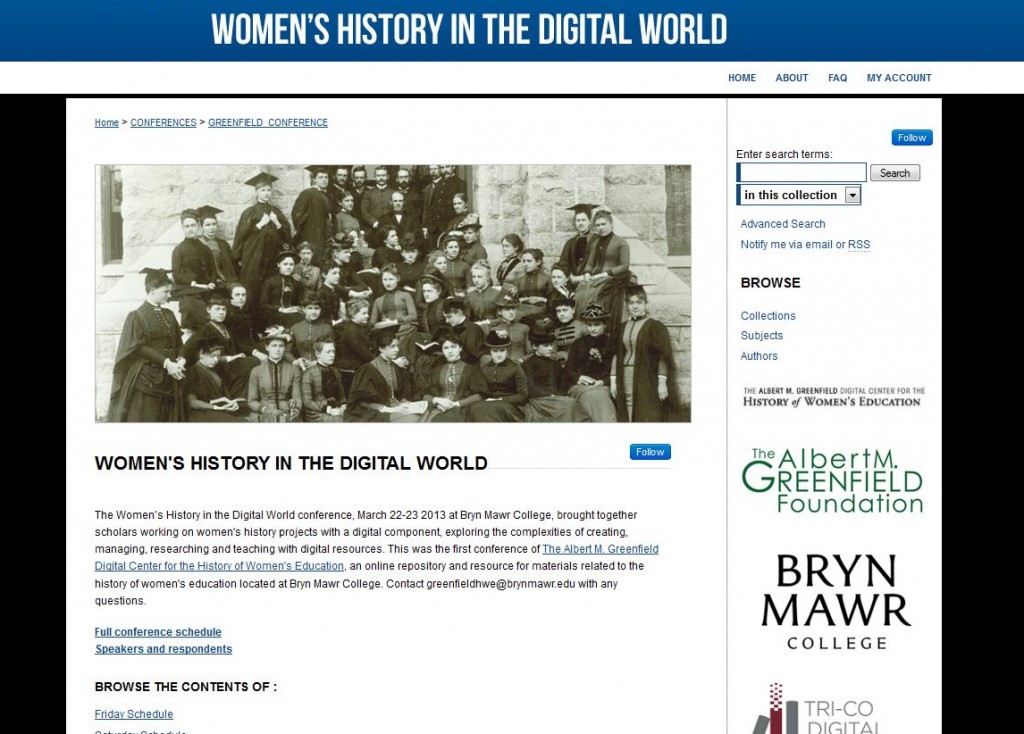

The popularity of the Women’s History in the Digital World conference repository continues – there have been over 300 full-text downloads from the repository so far. We are so proud of our wonderful contributors for sharing their work and hope anyone who hasn’t done so already will be inspired to. Plans for the next conference will be going into gear in the fall, so keep an eye out for updates and think about submitting an individual paper or a panel if you have been working on a collective project. You can also follow the recording of the conference by visiting our blog post which detailed the Twitter archive, Storify and blog posts on the conference and you can listen to Professor Laura Mandell’s inspiring keynote here.

The popularity of the Women’s History in the Digital World conference repository continues – there have been over 300 full-text downloads from the repository so far. We are so proud of our wonderful contributors for sharing their work and hope anyone who hasn’t done so already will be inspired to. Plans for the next conference will be going into gear in the fall, so keep an eye out for updates and think about submitting an individual paper or a panel if you have been working on a collective project. You can also follow the recording of the conference by visiting our blog post which detailed the Twitter archive, Storify and blog posts on the conference and you can listen to Professor Laura Mandell’s inspiring keynote here.

As some of you know, I will be going on maternity leave for this summer, so if you wish to get in touch with someone about the work, please contact the Center’s Research Assistant, Evan McGonagill, who will be managing communications throughout the summer (you can contact her through the general email address: greenfieldhwe@brynmawr.edu). There will be more blog posts and updates so don’t forget to follow us on Twitter and to visit the Educating Women blog. You can comment on any blog post you see, and we always look forward to hearing your comments so stay in touch, and happy summer!