Bryn Mawr Special Collections is jumping on the edit-a-thon bandwagon!

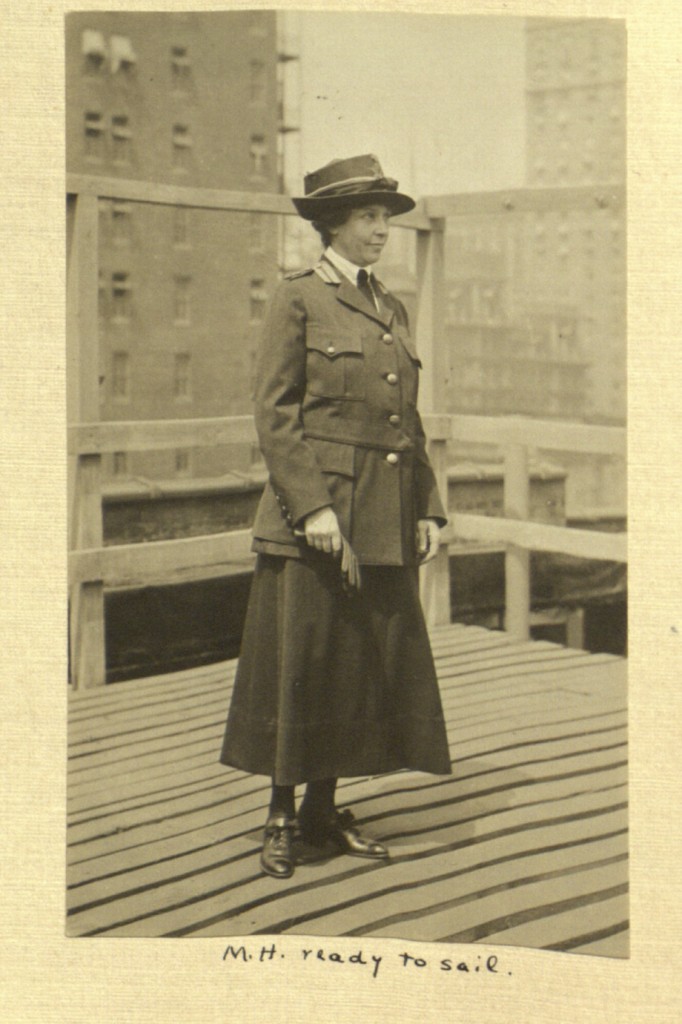

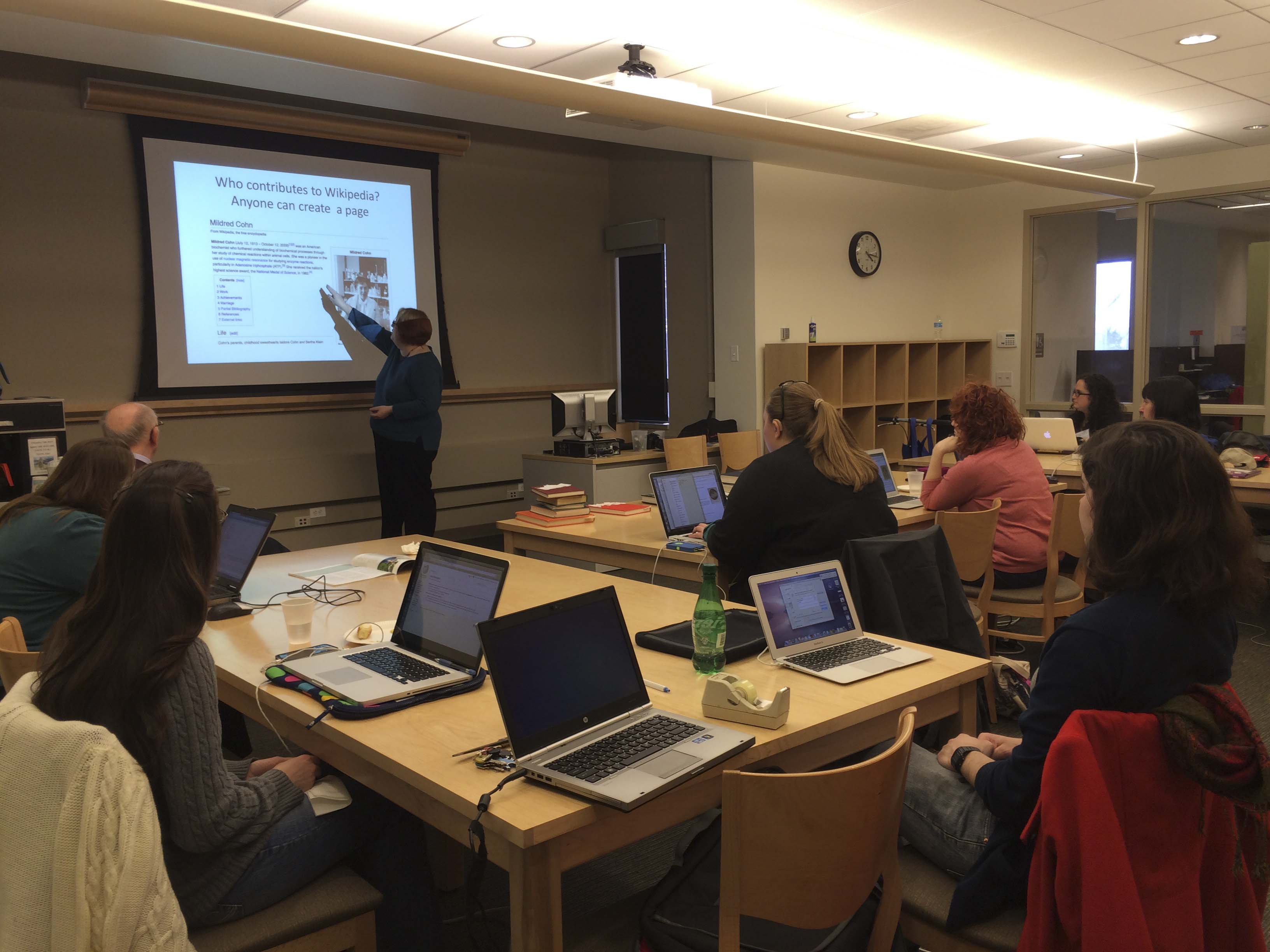

Staff members participating in the edit-a-thon, January 10th 2013

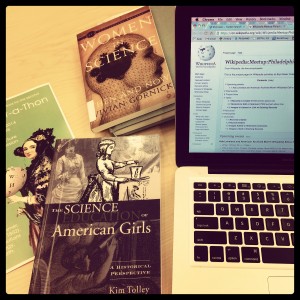

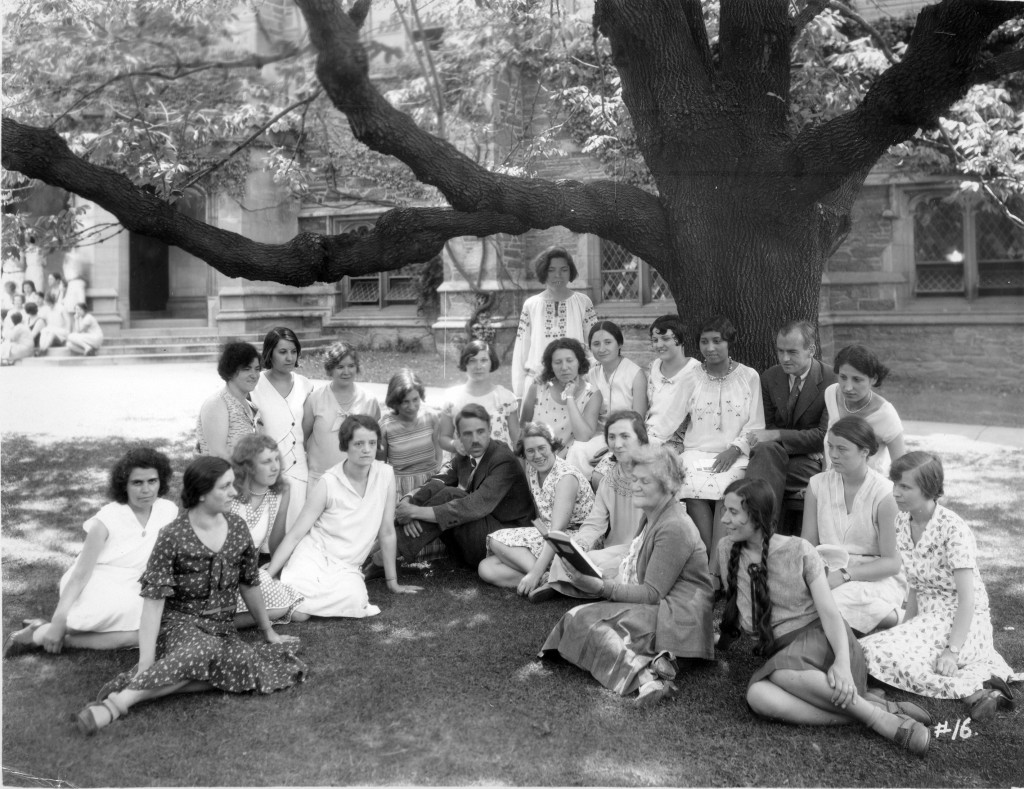

This past Friday, we held a small trial run Wikipedia edit-a-thon: a gathering at which people work on adding to or editing articles on the encyclopedia website, often organized around a specific topic. The goal of the endeavor is multifaceted: we want to add information pertinent to our collections in order to increase awareness of our holdings; to improve general knowledge by enhancing existing articles with additional information; and to add to the global body of accessible knowledge on women and women’s history. I have begun writing a new article for Hilda Worthington Smith (not yet posted), a Bryn Mawr alumna who played a lead role in The Summer School for Women Workers in Industry in the 1920s and ’30s. Other colleagues added new articles, improved existing articles by adding links to our holdings, and interlinked between articles. This initial trial helped us to to gauge the challenges, feasibility, and possible benefits of holding similar events in the future with a broader group of participants.

Courtesy of Wikipedia.org

Why Wikipedia? Surely there are other channels by which we might accomplish these goals–channels that are more reputable, or more specialized. Our alumnae, for instance, would be more likely to read about highlights from our collections through the Alumnae Bulletin, researchers can find us through networks of finding aids and citations, and anybody with an internet connection can browse the Triptych and Triarte databases to view the art objects, images, and documents that we hold. But the draw of Wikipedia isn’t specialization–it’s precisely the opposite.

With the abundance of information available on the internet growing every second, people are relying increasingly on powerful aggregators like Google and sites like Wikipedia which provide a centralized source for general knowledge. This is valuable and useful, but also cause for concern. As the amount of information covered by these tools grows, they take on the illusion of completeness. The phenomenon is summed up aptly by Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales with the “Google test: ‘If it isn’t on Google, it doesn’t exist.'” (If a tree falls in a forest…) If it doesn’t exist on Wikipedia, the public perception is that it must not be very important.

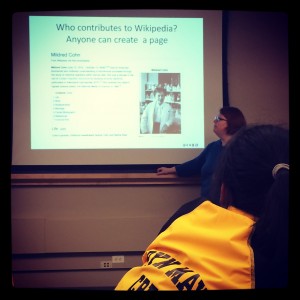

Professors are notoriously uneasy with their students’ reliance on Wikipedia, and have been known to decry its democratic structure as a free-for-all for self-appointed journalists spreading unreliable information. While the concern may be overblown (the site actually has strict rules about citation and regularly cleans out content of poor quality), it is true that Wikipedia is only as reliable as those who participate in writing and editing it. Like all sources, its assertions should be interrogated rather than blindly accepted. The legitimate fear is not that it is fallible, but that its readers will forget that it is so. Once we recognize it as an incomplete,  occasionally inaccurate, and highly mutable record, the conversation becomes much more interesting. If it is not a record of “everything,” what is it a record of? The diagram on the right is my interpretation of what it looks like to begin to refine our understanding of Wikipedia’s relation to wider cultural knowledge. I have never spoken to a person who actually believes the statement in stage 1, but my perception is that many people are stuck at stages 3 and 4. Versions of the statement in stage 5 have recently emerged at the center of dialogue in feminist and digital communities about the role that Wikipedia plays in our cultural knowledge, the assertion among feminists being that it both reinforces systemic problems and also provides opportunities for reform, which it becomes our responsibility to take.

occasionally inaccurate, and highly mutable record, the conversation becomes much more interesting. If it is not a record of “everything,” what is it a record of? The diagram on the right is my interpretation of what it looks like to begin to refine our understanding of Wikipedia’s relation to wider cultural knowledge. I have never spoken to a person who actually believes the statement in stage 1, but my perception is that many people are stuck at stages 3 and 4. Versions of the statement in stage 5 have recently emerged at the center of dialogue in feminist and digital communities about the role that Wikipedia plays in our cultural knowledge, the assertion among feminists being that it both reinforces systemic problems and also provides opportunities for reform, which it becomes our responsibility to take.

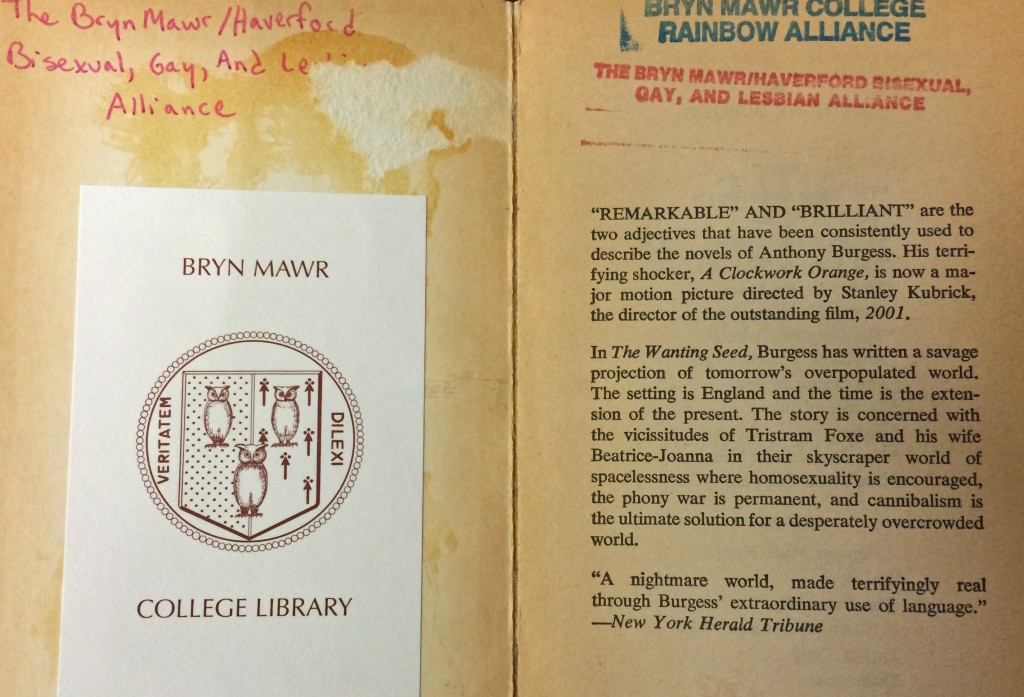

While Bryn Mawr Special Collections will use the site to provide better access to our collections in general, the edit-a-thons also align particularly with the mission of The Greenfield Digital Center to build recognition of women in digital spaces. It is important to ensure that women and minority voices have a presence on Wikipedia, simply because it is so many people’s main reference for information–otherwise we risk losing sight of them entirely. Last Fall, our former Director Jennifer Redmond led a history class through the process of improving the Wikipedia article for M. Carey Thomas, demonstrating the incompleteness of what some view as the “official” record and the importance of taking the steps we can to fill in the gaps.

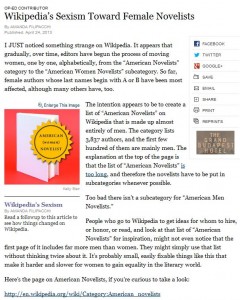

Filipacchio’s New York Times Op-Ed

The volume of the conversation around gender in Wikipedia rose to a new pitch in April 2013 when Amanda Filipacchi noticed a disturbing trend: Wikipedia editors were gradually moving women from the general “American Novelists” listing to a marginal sub-category called “American Women Novelists,” leaving the original list, with name still ungendered, exclusively male. This observation raised crucial questions about the visibility of marginalized groups and the responsibility of editors and others to consciously address these problems. Her article, and the flood of ensuing coverage, brought new focus to a conversation about the under-representation of women on the site–both as subjects of content and in their roles as contributors. (A useful summary of the conversation can be found here.) The dialogue became an opportunity to reflect on the systemic nature of sexism, and the insidious feedback loop between structural problems in society and sources like Wikipedia: culture reinforces its imbalances by creating a record that reflects them, replicating the existing flaws like mutated DNA as it constantly remakes itself in the image of the problematic record. In other words, rather than a record of the world itself, Wikipedia serves as a mirror of our worldview with the power to either perpetuate or transform the problems it contains.

Courtesy of Postcolonial Digital Humanities, http://dhpoco.org

The Importance of Participation: the best way to fix it is to get our feet wet and address the matter at the source of the controversy, and organized efforts like The Rewriting Wikipedia Project are taking the reigns. The under-representation of women, gender non-conforming individuals, people of color, and others on Wikipedia is a site-specific manifestation of a universal problem. By adding to and editing Wikipedia, therefore, we address two areas in need of change: we fill in the gaps that exist between the site and our culture, adding in those who have been left out of the encyclopedia but have achieved recognition by society outside the digital realm. (Examples include the women mentioned in this article who have won prestigious STEM awards but go unrecognized on Wikipedia). Additionally, in adding in those who have been neglected either on the site or in general society, we take steps towards correcting those lacks in the culture itself, from beyond and before Wikipedia: we reassert the importance and visibility of the marginalized, affirming their place in history and their right to be known. Because of its open structure, Wikipedia is more than just a mirror of the status quo: it is also a potential locus of powerful change.

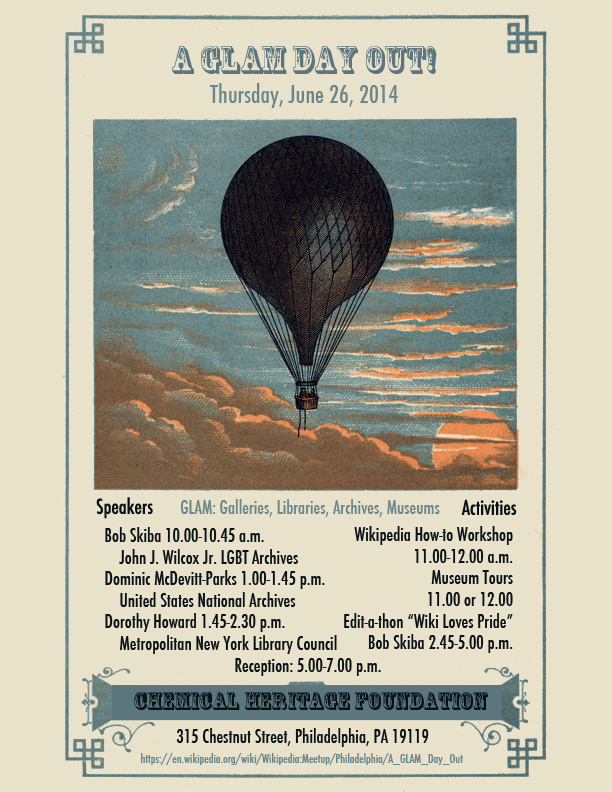

Therefore, edit! Setting up a Wikipedia account is easy. Learning the editing protocol is a little bit more of an investment, but can be easily covered within an hour. By taking an organized approach to adding information into the site we can support each other as we learn how to edit, ask questions about material and learn about the collections, and make a difference in the visibility of Bryn Mawr’s remarkable collections and of women’s accomplishments in history. Edit-a-thons have been picking up all over the world, with growing frequency in past years, and we plan on holding another one in March to coincide with a Seven Sisters series of edit-a-thons for Women’s History Month. In the meantime, we will be publicizing and participating in events like the upcoming Art and Feminism edit-a-thon* on Saturday, February 1st, in order to continue to get our feet wet and learn the ins and outs of the site.

If you’re interested in getting involved with a future event, please write to us at GreenfieldHWE@brynmawr.edu and follow us on Twitter! @GreenfieldHWE

*Update: remote participants are more than welcome at edit-a-thons, but if you’re in a major city chances are good that you could participate in the Art and Feminism edit-a-thon in person. More fun and usually free food! Check this page for a full listing of participating organizations to see if there is someone hosting a gathering near you.

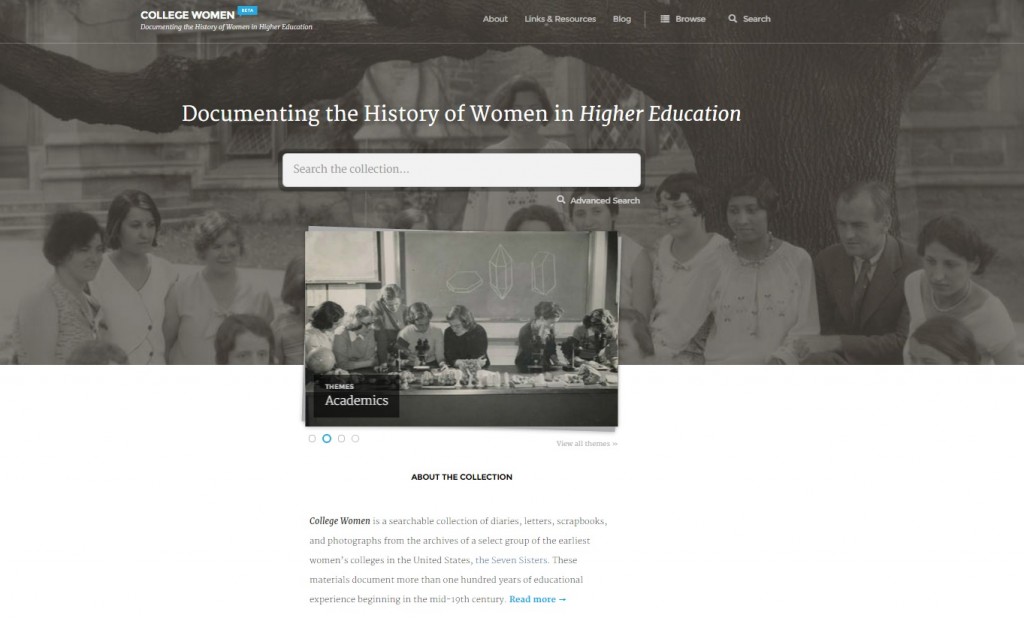

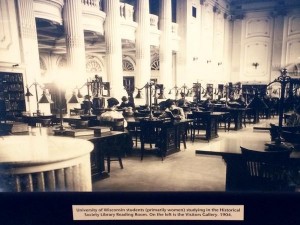

In Summer, 2015 we announced the beta launch of the cross-institutional archives portal College Women: Documenting the History of Women in Higher Education (collegewomen.org), a collaboration between the institutions once — and often still — known as the “Seven Sisters.” The site development was funded by a Foundations planning grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, and allowed us to begin imagining a resource that could serve both researchers and the casual browser interested in the shared histories of women’s education at some of the first U.S. women’s colleges in the Northeast. Today, we can now share that the National Endowment for the Humanities has recently awarded a Humanities Collections and Reference Resources grant to Bryn Mawr College that will allow us to expand the digitization project with our seven partner institutions beginning in Summer 2016.

In Summer, 2015 we announced the beta launch of the cross-institutional archives portal College Women: Documenting the History of Women in Higher Education (collegewomen.org), a collaboration between the institutions once — and often still — known as the “Seven Sisters.” The site development was funded by a Foundations planning grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, and allowed us to begin imagining a resource that could serve both researchers and the casual browser interested in the shared histories of women’s education at some of the first U.S. women’s colleges in the Northeast. Today, we can now share that the National Endowment for the Humanities has recently awarded a Humanities Collections and Reference Resources grant to Bryn Mawr College that will allow us to expand the digitization project with our seven partner institutions beginning in Summer 2016.

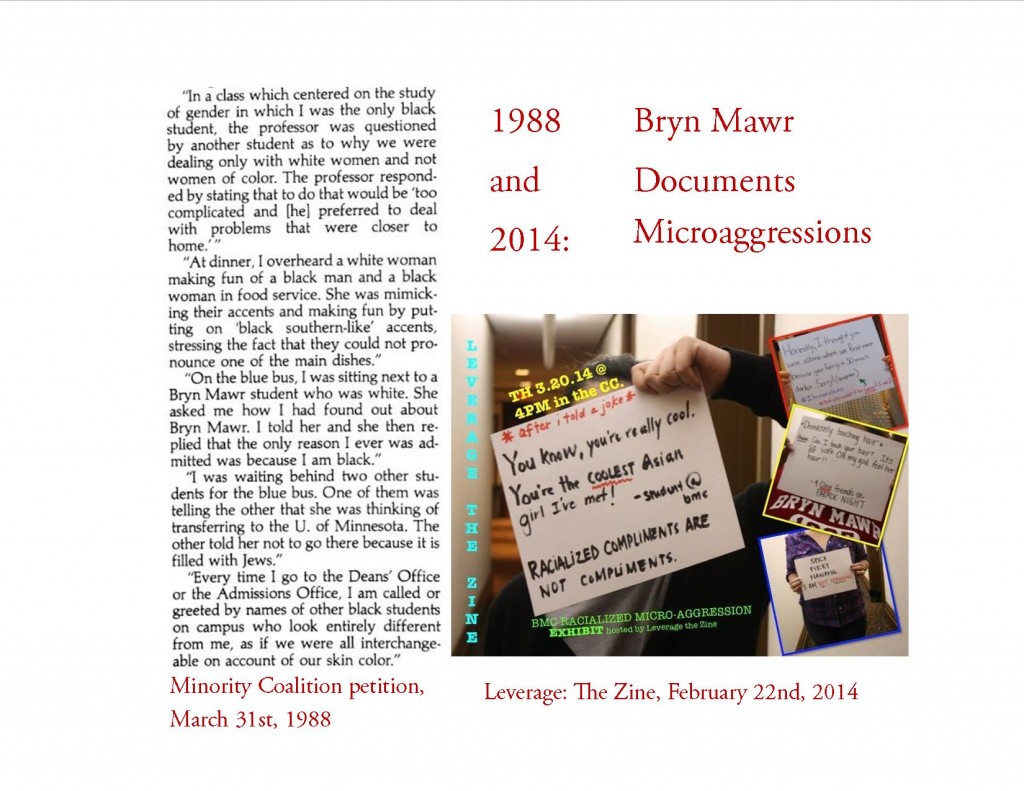

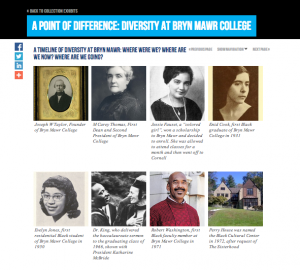

I do think that there are students on Bryn Mawr’s campus that felt/feel that way. It is not easy being a student of color at Bryn Mawr when you feel like you are not represented within SGA, the faculty of the college, and even administration. I think that feelings of resentment built up for many students that rose to the surface last year, and although students rallied together around the issue of Perry House, emotions ran very high. The biggest complaint I heard from students last year was that they felt silenced; their thoughts and opinions were not being heard. I do however think that there was a major (positive) shift the moment President Cassidy and Interim Provost Osirim took over. President Cassidy immediately addressed student concerns and apologized for the college’s past mistakes, which had not been done before in a way that seemed sincere to students of color.

I do think that there are students on Bryn Mawr’s campus that felt/feel that way. It is not easy being a student of color at Bryn Mawr when you feel like you are not represented within SGA, the faculty of the college, and even administration. I think that feelings of resentment built up for many students that rose to the surface last year, and although students rallied together around the issue of Perry House, emotions ran very high. The biggest complaint I heard from students last year was that they felt silenced; their thoughts and opinions were not being heard. I do however think that there was a major (positive) shift the moment President Cassidy and Interim Provost Osirim took over. President Cassidy immediately addressed student concerns and apologized for the college’s past mistakes, which had not been done before in a way that seemed sincere to students of color.

This month, the

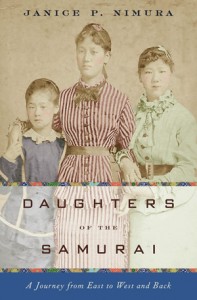

This month, the  Daughters of the Samurai describes the journey begun in 1871, of five young girls who were sent by the Japanese government to the United States. Their mission: learn Western ways and return to help nurture a new generation of enlightened leaders in Japan. Raised in traditional samurai households during the turmoil of civil war, three of these unusual ambassadors—Sutematsu Yamakawa, Shige Nagai, and Ume Tsuda—grew up as typical American schoolgirls. Upon their arrival in San Francisco they became celebrities, their travels and traditional clothing exclaimed over by newspapers across the nation. As they learned English and Western customs, their American friends grew to love them for their high spirits and intellectual brilliance. The passionate relationships they formed reveal an intimate world of cross-cultural fascination and connection. Ten years later, they returned to Japan—a land grown foreign to them—determined to revolutionize women’s education. Based on in-depth archival research in Japan and in the United States, including decades of letters from between the three women and their American host families, Daughters of the Samurai is beautifully, cinematically written, a fascinating lens through which to view an extraordinary historical moment.”

Daughters of the Samurai describes the journey begun in 1871, of five young girls who were sent by the Japanese government to the United States. Their mission: learn Western ways and return to help nurture a new generation of enlightened leaders in Japan. Raised in traditional samurai households during the turmoil of civil war, three of these unusual ambassadors—Sutematsu Yamakawa, Shige Nagai, and Ume Tsuda—grew up as typical American schoolgirls. Upon their arrival in San Francisco they became celebrities, their travels and traditional clothing exclaimed over by newspapers across the nation. As they learned English and Western customs, their American friends grew to love them for their high spirits and intellectual brilliance. The passionate relationships they formed reveal an intimate world of cross-cultural fascination and connection. Ten years later, they returned to Japan—a land grown foreign to them—determined to revolutionize women’s education. Based on in-depth archival research in Japan and in the United States, including decades of letters from between the three women and their American host families, Daughters of the Samurai is beautifully, cinematically written, a fascinating lens through which to view an extraordinary historical moment.”

The October talk featuring Greenfield Director Monica Mercado, Rachel Appel (Bryn Mawr College Digital Collections Librarian) and Joanna DiPasquale (Vassar College Digital Initiatives Librarian) is now online via

The October talk featuring Greenfield Director Monica Mercado, Rachel Appel (Bryn Mawr College Digital Collections Librarian) and Joanna DiPasquale (Vassar College Digital Initiatives Librarian) is now online via