Embodiment, or in this context, examining the physiological arguments made about women’s education in the past is the subject of this blog post, which relates to a previous post by Michelle Smith on the philosophical and theoretical writings expounding the detrimental physical effects education would have on women’s health. This is a theme we are continuously interested in as many of the early entrants to Bryn Mawr and other colleges that permitted women to attend had to battle notions of their physical and mental inferiority to be taken seriously as students and scholars. This topic is also related to project assistant Jessy Brody’s work on physical culture and sports at Bryn Mawr College which will appear as an exhibit on our site in the coming months.

Physical education at women’s colleges became a focus of attention at the end of the nineteenth century. As the Recent HerStory site posting on Senda Berenson Abbott of Smith College by Frances Davey, womanly grace and athleticism were ideas that were trying to be combined when Berenson introduced basketball at the college. As Davey argues, the emphasis on activity – both in a physical sense and a public one – became characteristic of what was termed ‘the New Woman’ at the turn of the twentieth century. Physical education and a more public identity for women were intertwined ideas in society and thus physicality for women was incredibly important in re-imagining roles for women through their acquisition of higher education.

Gender, education and embodiment is a subject of interest not only because the statements made about the physically detrimental effects of higher learning on women’s bodies seem absurd in today’s culture of thriving women in universities, but also because notions of gender appropriate educational behavior changed over time.

Gender, education and embodiment is a subject of interest not only because the statements made about the physically detrimental effects of higher learning on women’s bodies seem absurd in today’s culture of thriving women in universities, but also because notions of gender appropriate educational behavior changed over time.

Some of this material will form the basis of an exhibit next year which will be shown in the Rare Book Room at Canaday Library. Although I am currently sketching out the exhibit narrative, I’m interested in portraying the debates for and against women’s higher education and in telling the story of women’s progress at third level from past exclusion to present domination. The exhibit will trace the narrative arc of women’s progression from gaining access to being taken seriously as academics and scholars.

Mary Kelley (an advisory committee member to our project and a Professor at the University of Michigan) has completed ground breaking work on women and reading which has shed light on the importance of literacy, education and the cultivation of the mind for women’s ability to enter the public sphere in their own right (in the excellent Learning to Stand and Speak). Yet the struggle of women in the past was not merely literacy but overcoming the embedded social prejudices which posited education outside the home for women as immoral, subversive and socially stigmatizing. As detailed in M. Carey Thomas’ own words, her mother’s friends would have been less shocked had she run away to marry the coach man than over her desire to pursue higher education in Germany.

Mary Kelley (an advisory committee member to our project and a Professor at the University of Michigan) has completed ground breaking work on women and reading which has shed light on the importance of literacy, education and the cultivation of the mind for women’s ability to enter the public sphere in their own right (in the excellent Learning to Stand and Speak). Yet the struggle of women in the past was not merely literacy but overcoming the embedded social prejudices which posited education outside the home for women as immoral, subversive and socially stigmatizing. As detailed in M. Carey Thomas’ own words, her mother’s friends would have been less shocked had she run away to marry the coach man than over her desire to pursue higher education in Germany.

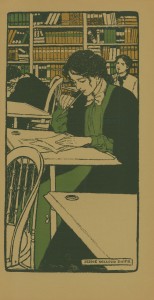

Serious application of women’s minds to the study of academic works, as opposed to ‘appropriate’ forms of feminine literature, led some to argue that women’s physical health would be severely compromised, as if exercising their brain would diminish their physical capacity.  Notions of this kind emanated from gendered ideas of women’s corporeality and greater susceptibility to physical ailments in convergence with beliefs of the diminished intellectual capacity of women. Therefore, following this logic, any ‘over straining’ of a woman’s limited mental capacities would result in irreversible physical damage, or certainly physical incapacities while the woman persisted with such ‘mental strain’.

Notions of this kind emanated from gendered ideas of women’s corporeality and greater susceptibility to physical ailments in convergence with beliefs of the diminished intellectual capacity of women. Therefore, following this logic, any ‘over straining’ of a woman’s limited mental capacities would result in irreversible physical damage, or certainly physical incapacities while the woman persisted with such ‘mental strain’.

Dr. Edward Hammond Clarke’s 1873 treatise, Sex and Education (available free online here) made a direct connection between women’s fertility and their modes of study. Clarke argued that the body could not cope with two physical processes at the same time, and applied this to both boys and girls”

“The physiological principle of doing only one thing at a time, if you would do it well, holds as truly as the growth of the organization as it does of the performance of any of its special functions. If excessive labor, either mental or physical, is imposed upon children, male or female, their development will be in some way checked.” (Pg. 40-41)

Extending this argument to girls at the age of puberty, Clarke argued that the development of women’s fertility organs (referred to by Clarke euphemistically as her ‘organization’) was incompatible with intense scholarly study and he stated numerous cases where women’s fecundity was put at risk or negated entirely by study:

“There have been instances, and I have seen such, of females, in whom the special mechanism we are speaking of remained germinal, — undeveloped. It seemed to have been aborted. They graduated from school or college excellent scholars, but with undeveloped ovaries. Later they married, and were sterile.” (Pg. 39)

There are a number of ideas and assumptions contained within this short quotation that illuminate medical thinking on women’s health and education: firstly, that a person’s intellect and education could affect the physical development of the body to such an extent as to eliminate the growth of sex organs; secondly, that because the brain and the body could not both operate at optimum level simultaneously, girls should abandon their academic studies while going through critical physical development periods; that girls risked their health and future fertility by persisting on studying at the same time and at the same level as boys; and that the natural path for women was as mothers, not scholars.

As with other arguments, much of this rhetoric overtly or covertly referred to women’s fertility and its potential to be impaired by academic study or even engaging in thought or reading deemed to be too taxing. This was Mary Garrett’s experience;  Garrett, although wealthy and from a prominent family, was not allowed to study as M. Carey Thomas had, and yet her physical ailments (such as headaches, piles and an irregular menstrual cycle) were blamed on her wide ranging reading material. Her hopes to recover by following doctor’s orders are revealed in the following poignant passage in a letter to Thomas in December 1880 which Garrett wrote while on a trip to Cannes:

Garrett, although wealthy and from a prominent family, was not allowed to study as M. Carey Thomas had, and yet her physical ailments (such as headaches, piles and an irregular menstrual cycle) were blamed on her wide ranging reading material. Her hopes to recover by following doctor’s orders are revealed in the following poignant passage in a letter to Thomas in December 1880 which Garrett wrote while on a trip to Cannes:

“From my general condition the history of the past few years, my loss of memory, +c., he [the doctor] should have thought that there was some internal trouble, (displacement of the womb or something of the sort) and wants me when we go back <to the U.S.> to be examined again + assure my self that this is not the case_ (Of course I told him of my having been examined by Dr. Jacobs + the little that I c’d remember of what she said was the matter)—He thinks I sh’d simply go on leading as healthy a life as I can + attempt no study or work for certainly one or two years, perhaps longer but thinks that the chances are that I will eventually, although it may not be for ten years, get recover what mental power I ever had + that I need not be hopeless as to having by that time lost the power of using it _ not a brilliant prospect you see but something to look forward to _ You have never known the horror of not being able to think or to follow an argument or even remember one for a half hour_ Some bright Sport there are, however for what w’d I be if in this condition without the knowledge of the glorious things + thoughts there are + with out having gotten into the right path, although following it so feebly + haltingly. With such friend as I have + having their full sympathy and knowing a good deal of the true + the right, and with some appreciation at least of beauty, I ought not to kick too much against the pricks and <think> that the Fates are altogether cruel to me _ So you see you will have but a very stupid friend for perhaps ten years, and possibly to the end of my days, I wonder whther yr. patience will stand such a test!”*

The ‘prescription’ for Garrett’s health troubles are to exclude all level of study and reading of the materials she liked so much (they were a very literary circle of friends) for a period of one to two years or perhaps longer, which again points to the connection made by those such as Clarke that mental strain caused physical strain, particularly in women it seems. Garrett’s last words in this excerpt are poignant – she fears that her intellectual and memory capacities will be affected for many years ahead and possibly for the rest of her life and refers to herself as ‘stupid’, a designation none who knew her or have assessed her since would ever assign to her.

The ‘prescription’ for Garrett’s health troubles are to exclude all level of study and reading of the materials she liked so much (they were a very literary circle of friends) for a period of one to two years or perhaps longer, which again points to the connection made by those such as Clarke that mental strain caused physical strain, particularly in women it seems. Garrett’s last words in this excerpt are poignant – she fears that her intellectual and memory capacities will be affected for many years ahead and possibly for the rest of her life and refers to herself as ‘stupid’, a designation none who knew her or have assessed her since would ever assign to her.

The fusing of the physical and mental was of course a gendered construct – no such fears existed about men damaging their virility because of their educational attainment. This was, in the logic of such arguments, because education at a higher level was a natural part of a man’s life and indeed would elevate him socially, spiritually and mentally. Embracing the ‘unnatural’ role of an educated woman was therefore met with resistance as well as courage by those women, M. Carey Thomas included, who pursued their desire for higher learning in the late nineteenth century.

What we can learn from this history is that women have overcome many obstacles in achieving access to education, surmounting real and philosophical challenges to their intellectual capacity and their physical health. Without these pioneering women it is doubtful that the bountiful array of opportunities for women in society would exist today and for that legacy we are truly thankful.

*With thanks to Amanda Fernandez, Special Collections student worker, for her work on transcribing the Garrett-Thomas letter quoted above.